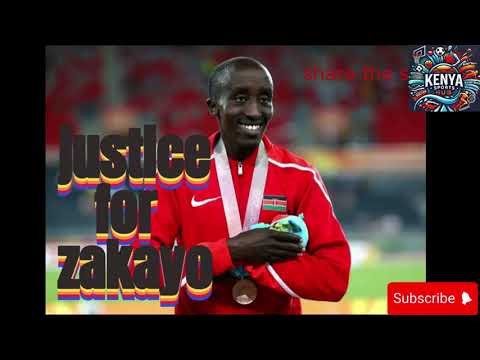

Edward Zakayo wasn’t just a runner; he was the wind made flesh. Hailing from the arid scrublands of a remote minority community of narok county in kenya towards tanzania boarder, his speed was his only inheritance, a blistering gift that had carried him from dusty local track meets to the international stage. After a breakthrough season, he was due back in Nairobi for the final World Championship trials, the final step before true global fame.

His journey started well, but ended in disaster. Somewhere between Dubai and JKIA, the bright red suitcase containing his entire life—his spiked shoes, his training logs, his medication prescriptions, and, most crucially, his primary Kenyan SIM card and a small notebook detailing his exact training camp whereabouts—vanished off the Emirates carousel.

Frantic, Edward filed the report, clutching the flimsy claim ticket. The airline staff were apologetic but vague. He tried to contact his agent, but his travel phone was useless without the SIM, and his limited funds meant replacing both the phone and the essential contacts was a delay of days. He settled in a cheap Nairobi hostel, waiting for his meager savings to clear, desperately trying to coordinate with borrowed, unfamiliar numbers.

It was during those critical 72 hours that the anti-doping officers arrived at his registered training camp, miles away in Iten and elgoiyo marakwet. Two separate, mandatory Whereabouts Tests were scheduled. They called the number he had provided. It rang out, an electronic, unfeeling silence. They emailed the address listed with his Athletics Kenya (AK) file. That email address was only accessible through the lost phone.

The result was swift and unforgiving: three missed tests, classified as a Whereabouts Failure, equating, in the cold eyes of the doping regulators, to an attempt to evade testing. Edward was provisionally suspended. His desperate appeals, explaining the lost luggage, the SIM card failure, and the paper trail of the police report, were dismissed as the predictable lies of a guilty man. The rules, AK officials stated, were absolute: accountability was must.

Then, three years and four months later, a formal, apologetic email arrived from Emirates. The red suitcase had been found in a warehouse in Frankfurt, mistakenly routed during a complex baggage transfer. It was delivered to Edward’s old address in Nairobi. Inside, everything was intact: the shoes, the logbooks, and the dead SIM card, resting next to the handwritten note detailing his location for the exact dates he missed the tests.

With the physical evidence—the original baggage claim, the police report, and the airline’s own belated admission of fault—Edward raced back to Athletics Kenya’s headquarters. He laid out the case: the lost SIM was the silent killer of his career, and the airline’s monumental error was the root cause.

But the Athletics Kenya panel was unmoved. “Three years have passed, Edward,” the chairman stated, his voice flat. “The suspension stands. You were not contactable. The system cannot make exceptions for logistical errors.” He was denied entry into the national trials, his only path back.

“It wasn’t the doping rule that killed me,” he whispered to himself, standing outside the gates of the stadium where his peers were now running. “It was the poverty. It was the silence of a lost SIM card, multiplied by my minority tribe, multiplied by the simple fact that I had no one important to speak my name.” The world of elite athletics had deemed his tragedy insignificant, a footnote in the rigorous pursuit of clean sport, simply because he lacked the privilege to make his truth matter. @WorldAthleticsFaith Kipyegon maintains her reign in the 1500m, winning her fourth world title at the distance on the fourth day of action in Tokyo. 🇨🇦’s Ethan Katzberg smashes the hammer throw championship record and Hamish Kerr completes his set of golden global medals. Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone storms to a new American 400m record in the semifinals, while Cordell Tinch powers to his first global gold in the men’s 110m hurdles final. That and much more in the highlights of day 4 at the World Athletics Championships Tokyo 25.

@Olympics

USA all the way in the 200m finals as Noah Lyles wins her 4th 200m gold medal, while Melissa Jefferson-Wooden wins an impressive sprint double, the first since Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce in 2013. Femke Bol retains her 400m hurdles title with a world-leading 51.54 and Olympic champion Rai Benjamin adds the world title to his long list of honours. Portugal’s Pedro Pichardo comes in clutch during the men’s triple jump final with a phenomenal 6th and final attempt. That and more in the recap of the 7th day of action at the World Athletics Championships Tokyo 25.

Catch up on the highlights of the first day of action at the World Athletics Championships Tokyo 25 including the 35km race walk for men and women, men’s shot put final, women’s 10,000m final, the mixed 4x400m relay .

Edward, But school. [Music] It’s okay 2017. [Music] And the runners out now for heat two, the boys 3,000 m. The first round boys 3,000 m. He too is underway in Kazarani. Edward Zakayo the national champion at this age range sub 8minute runner looking very comfortable in front of the Ethiopian Milgassa Mingesa. But Zakayo has got more in his legs as he comes to the finish. It’s a Kenyon victory in the heats of the 30,000 meters in 80487 with five will qualify of course. Tako is saluting the crowd.

3 Comments

Edward Zakayo wasn't just a runner; he was the wind made flesh. Hailing from the arid scrublands of a remote minority community, his speed was his only inheritance, a blistering gift that had carried him from dusty local track meets to the international stage. After a breakthrough season, he was due back in Nairobi for the final World Championship trials, the final step before true global fame.

His journey started well, but ended in disaster. Somewhere between Dubai and JKIA, the bright red suitcase containing his entire life—his spiked shoes, his training logs, his medication prescriptions, and, most crucially, his primary Kenyan SIM card and a small notebook detailing his exact training camp whereabouts—vanished off the Emirates carousel.

Frantic, Edward filed the report, clutching the flimsy claim ticket. The airline staff were apologetic but vague. He tried to contact his agent, but his travel phone was useless without the SIM, and his limited funds meant replacing both the phone and the essential contacts was a delay of days. He settled in a cheap Nairobi hostel, waiting for his meager savings to clear, desperately trying to coordinate with borrowed, unfamiliar numbers.

It was during those critical 72 hours that the anti-doping officers arrived at his registered training camp, miles away in Iten. Two separate, mandatory Whereabouts Tests were scheduled. They called the number he had provided. It rang out, an electronic, unfeeling silence. They emailed the address listed with his Athletics Kenya (AK) file. That email address was only accessible through the lost phone.

The result was swift and unforgiving: three missed tests, classified as a Whereabouts Failure, equating, in the cold eyes of the doping regulators, to an attempt to evade testing. Edward was provisionally suspended. His desperate appeals, explaining the lost luggage, the SIM card failure, and the paper trail of the police report, were dismissed as the predictable lies of a guilty man. The rules, AK officials stated, were absolute: accountability was paramount.

Edward’s world collapsed. He became a ghost, training alone on dusty roads, watching his rivals achieve the dreams that had been stolen from him. The years blurred—one, two, then three—of poverty, rejection, and the crushing weight of suspicion.

Then, three years and four months later, a formal, apologetic email arrived from Emirates. The red suitcase had been found in a warehouse in Frankfurt, mistakenly routed during a complex baggage transfer. It was delivered to Edward’s old address in Nairobi. Inside, everything was intact: the shoes, the logbooks, and the dead SIM card, resting next to the handwritten note detailing his location for the exact dates he missed the tests.

With the physical evidence—the original baggage claim, the police report, and the airline's own belated admission of fault—Edward raced back to Athletics Kenya's headquarters. He laid out the case: the lost SIM was the silent killer of his career, and the airline’s monumental error was the root cause.

But the Athletics Kenya panel was unmoved. "Three years have passed, Edward," the chairman stated, his voice flat. "The suspension stands. You were not contactable. The system cannot make exceptions for logistical errors." He was denied entry into the national trials, his only path back.

Crushed, Edward walked away, not just beaten by bureaucracy, but consumed by a deeper, colder realization. He saw the sons and daughters of influential families in the sport, whose minor infractions were smoothed over by a phone call to the right person. He saw the difference between his position and theirs: he was Edward Zakayo, a boy from a tiny, unrepresented tribe, with no politician to lobby for him, no wealthy relative to hire a high-powered attorney, and certainly no leadership figure from his community with the clout to challenge the official narrative.

"It wasn't the doping rule that killed me," he whispered to himself, standing outside the gates of the stadium where his peers were now running. "It was the poverty. It was the silence of a lost SIM card, multiplied by my minority tribe, multiplied by the simple fact that I had no one important to speak my name." The world of elite athletics had deemed his tragedy insignificant, a footnote in the rigorous pursuit of clean sport, simply because he lacked the privilege to make his truth matter.

very unfortunate..let the president intervene

justice justice….share across all platforms