This continues a series devoted to the 2025 Walker Cup from September 5-7. Previous editions looked at the 16th hole and 18th hole. This year’s squads are detailed here.

Since this year’s Walker Cup host site opened in 1928, collective wisdom has insisted that any old schmuck with a handicap lower than 36, at least one eye, and magazine panelist business card could have taken Marion Hollins’ marching orders, accommodated financial backer Samuel Morse’s demands, worked from Seth Raynor’s first routing, and proceeded to design something comparable to what Alister MacKenzie, Robert Hunter, and The American Golf Course Construction Company pulled off at Cypress Point.

Not a chance.

A century removed from the 1925 to 1930s golf architectural gold rush that saw the art enjoy an incredible five-year burst of American designs inspired by National Golf Links and Pine Valley, masterworks like Cypress Point employed innovative techniques and design lessons learned to propel the art forward. This resulted in seemingly uber-natural works that “looked like they’ve been there forever,” but with a lot going on under the hood. By employing new tools and driven by a desire to do right by the canvases they were handed, several architects produced sophisticated designs capable of exciting golfers for generations.

The Great Depression put a sad and far-too-damaging halt to the guiding spirit of that robust period. One that in California alone saw the creation of Cypress Point, a radical overhaul of Pebble Beach, Riviera, Bel-Air, and Pasatiempo. Even more remarkable? All were real estate developments.

When course construction resumed after World War II, the approach to financing, building, and designing courses within similar development schemes emphasized a mass-production, hard-is-good approach that protected land devoted to home sales. Those pesky details that affect golf shots or the overall experience became way less important. Armed with mass earthmoving tools, any craftsmanship or devotion to building a seemingly natural course full of intrigue gave way to a depressing uniformity.

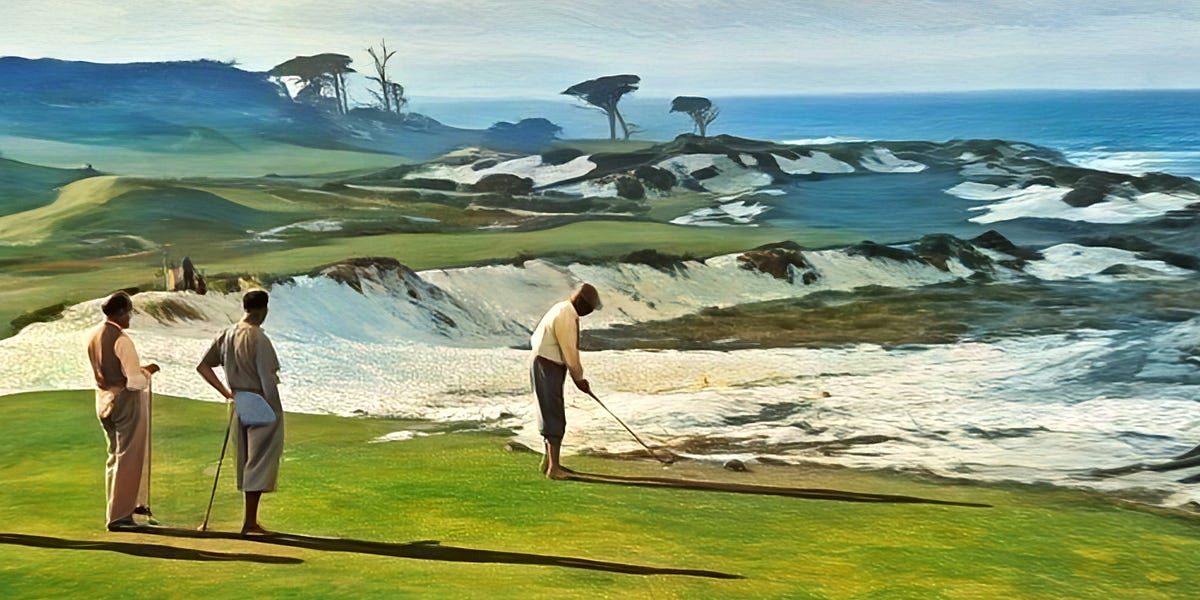

Robert Hunter and Alister MacKenzie during construction of Cypress Point

Robert Hunter and Alister MacKenzie during construction of Cypress Point

As with any collective artistic effort that ages gracefully, a golf architectural masterpiece happens after a mysterious brew of vision, patience, politics, creativity, luck, and rich imaginations are encouraged to create something out of the ordinary. Those merry design bands who created timeless works were almost always shepherded by get-it-done types who also knew when to shut up and let the painters paint. The maestro, a.k.a the golf architect, has to juggle the business needs with artistry and utility to create a finished product of permanence that inspires exuberance. Or, at the very least, a desire of golfers to want to play the course again.

Early rendering showing many holes never built but displaying aggressive real estate plans ultimately unrealized

Early rendering showing many holes never built but displaying aggressive real estate plans ultimately unrealized

MacKenzie was at the center of these driving forces when the Cypress Point project received the necessary support to finally break ground. He brought a different personality to the job than his predecessor, Raynor, who had a portfolio of incredible works and big-name backers in Hollins and H.J. Whigham. But as a non-golfer engineer, Raynor’s best work amounted to the music equivalent of an ingenious cover artist. Raynor took the basics of “template” holes, taught to him by C.B. Macdonald, and regularly put new twists on those wherever he went. Raynor took difficult sites and made most of them (sorry, Lido) functional. But he was not an artist nor a salesman of MacKenzie’s ability. He could not have pulled off what MacKenzie’s team accomplished.

As a golf course site, Cypress Point had the usual site quirks related to soil, irrigation, and weather. Several holes required manufacturing that remains indecipherable today. Microclimates and differences in soil forced decisions about what kind of embellishments should be made to bring out the best features and to never do aesthetic battle with the dunes, cypress, pines, and ocean front holes.

That’s a fancy way of saying that Cypress Point did not need an architect to come in, play his Redan, Double Plateau, and close out the encore with a Biarritz. Nor would his deep, straight-lined, grass-faced bunkers have worked on a site of such unusual beauty.

MacKenzie was in full world-traveler mode when he got the job. But he still spent two long stints on site during construction (as he did at Augusta). Hunter Sr., one of the more interesting characters in golf history thanks to his wealth, interests, writing, and extreme gravitas for a construction site manager, dealt with much of the planning, salesmanship, and daily supervision. If he was not around, his son and their shaping team arrived prepared to build something special. They had come from the Meadow Club and other San Francisco area projects, prepared to take things to another level.

Like a trusty group of session players who can play anything or improvise when called upon, the American Golf Course Construction crew could adapt to the inevitable hiccups and last-minute pivots of a golf course construction project. The Cypress job involved big personalities, but at least they were looking to build the best holes possible while also protecting real estate and tourism interests. Marion Hollins was there to guide the overall project as a visionary golfer who also could welcome A-list visitors, push the artisans, and inspire confidence in potential members or lot buyers.

Cypress Point’s finished course featured a highly unorthodox routing. Before various design norms like par 72, returning nines, and other mysterious rules led to so many forgettable courses, this one violated every unwritten edict. Not many of the holes penciled in by Raynor made the final cut, nor should that matter. The West Coast Chapter of the Seth Raynor Marching and Chowder Society might disagree.*