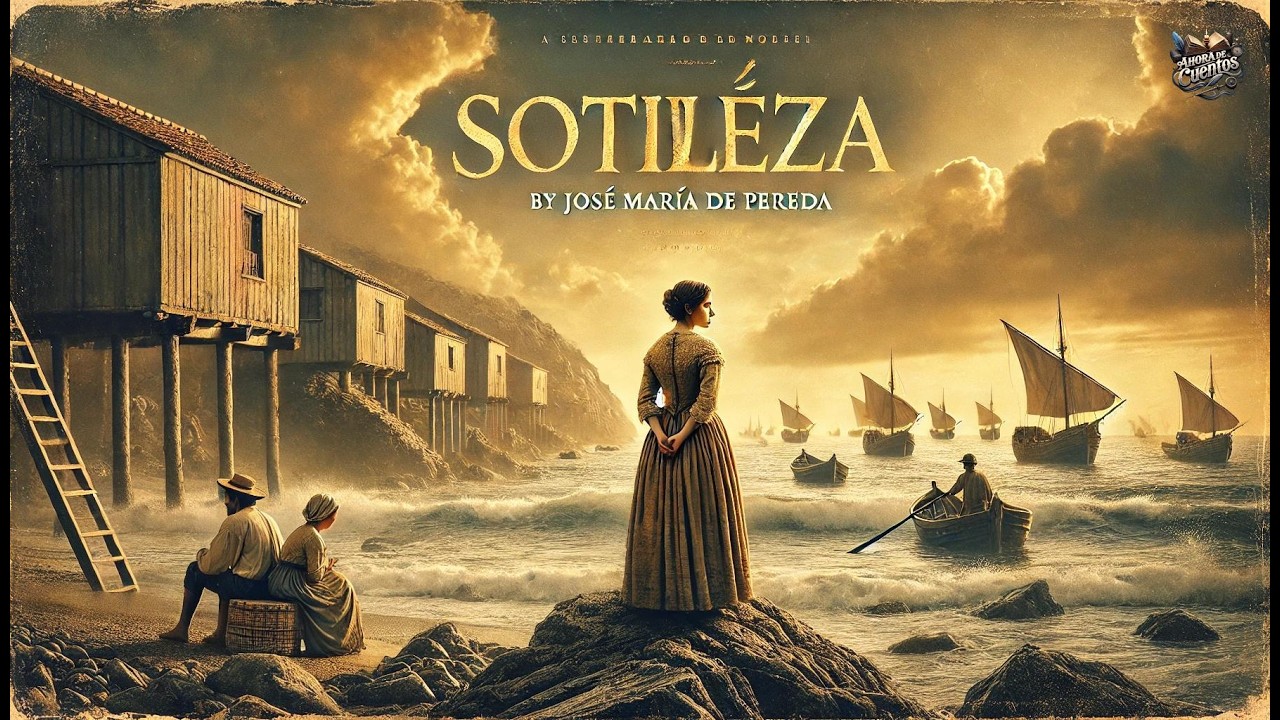

Sotileza de José María de Pereda 🌊📚

Sotileza is a novel that reflects rural life on the Cantabrian coast of the 19th century, exploring the complexities of love, social struggle , and the traditions of a deeply rooted community. Through his characters, José María de Pereda presents a story of passions and conflicts, in which destiny seems to be marked by the natural environment and local customs. Join us as we discover this fascinating work that takes us to the heart of Cantabria and the essence of the struggle for identity and survival. Chapter 1. CHRYSALIDS. The room was narrow, low-ceilinged, and gloomy; the walls, which had once been white, were blackened in parts, and a thick , almost stubborn tapestry of filth covered the worm-eaten floorboards. It contained a pine table, a battered calfskin armchair, and three rickety chairs; a crucifix with a sprig of dried laurel, two prints of the Passion, and a rosary from Jerusalem hung on the walls; A horn inkwell with a bird’s quill pen, a much-stitched old breviary, a black suede folder, a calendar, and a tin candlestick on the table; and, finally, a blue denim umbrella with a curved horn handle in one of the darkest corners. The room also had an alcove, at the back of which, through the gaps left open by a small Indian curtain that didn’t quite cover the rickety door, a poor bed could be seen, and on it a cloak and a tiled hat. Between the table, chairs, and umbrella, which filled the best part of the room, and half a dozen ragged children, who, leaning against the wall or pressing their noses against the window, or lying dislocated between two chairs and the table, occupied almost the rest, a priest in a patched cassock, slippers with black straps, and a threadbare velvet cap, was trying to move about with great difficulty. He was tall, somewhat stooped, with eyes that were too soft, which, through his horror of light, was the cause of the curvature of his neck; his nose was slightly bulging and red, his lips thick, his complexion rough and dark, and his teeth black. Among all these scoundrels, there was not a trace of a shoe or a full shirt ; all six were barefoot, and half of them were shirtless. One wrapped his entire skin in his father’s heavy, patched coat. Few of them had their legs straight: the one who had breeches didn’t have a jacket, and the only thing they all agreed on was their dirty faces, their hair in a mess, and their mangy, gory calves. The oldest of them was probably ten years old. They stank of a kennel. “Let’s see,” said the priest, flirtatiously nudging the one in the jacket, who was busy rubbing his nose against the balcony window. The boy was stocky, copper-skinned, cross-eyed, and had an enormous head, “who said the Creed?” The boy turned around, after squirting a thin thread of saliva at the window between two of his incisors, and shrugged his shoulders. “What do I know? ” “And why don’t you know, you little beast? Why do you come here? How many times have I told you that the apostles?” But _ab asino, lanam_… How many Gods are there?… “Gods?” repeated the person addressed, crossing his arms behind his back, so that he was left naked in the front; for the jacket had no buttons, nor buttonholes in which to fasten them even if it had. The priest noticed this and said, taking hold of the lapels and crossing one over the other: “Cover up that filth, swine!… And the buttons? ” “I don’t have them. ” “You must have been playing boat with them. ” “I had a sheet and I lost it this morning.” The priest went to the table and took a piece of twine from a drawer, with which he managed with great difficulty to fasten the two patched fronts of the jacket so that they covered the boy’s flesh. Then he repeated the question: “How many Gods are there?” “Well, there must be,” replied the person addressed, crossing his arms behind his back again, “eight or nine at full speed. ” “It rises from the depths!”… “Holy souls, what a beast!”… And how many people? The cross-eyed man stared, in his own way, fixedly at the priest, who also He looked at him as best he could, and answered, with every sign of being possessed by the greatest curiosity: “People!… What are people, you? ” “Blessed Saint Apollinaris!” exclaimed the simple priest , crossing himself, “so you don’t know what people are… what a person is!… Well, what are you? ” “Me?… I am Muergo. ” “Not even that much, because there are those on the beach with more understanding than you… What are people?” repeated the priest, facing the boy who followed Muergo on the right, also shirtless, but in breeches, although few and poor ones, less ugly than Muergo and not so hoarse of voice. This boy, not knowing what to reply, looked at the nearest one, who looked at the one following him; and they all looked at each other, with the same doubts painted on their faces. “So,” exclaimed the priest, turning to confront the man following Muergo, “you don’t know what you are either? ” “Yes, you are, Corflis!” replied the boy, believing he saw a clear way out of his predicament. “Then what are you? ” “Surbia. ” “That’s what I’d give you to burst, you beast! ” “And what are you?” added the priest, addressing another man, half -shirted, but without a jacket and very few trousers. “I am Sula,” replied the man addressed, who was blond and thin, which made his filth stand out more than his comrades’ tanned complexion. In this way, and trying to answer the same question, the other three boys in the room, namely Cole, Guarin, and Toletes, began to give their nicknames. Perhaps none of them knew their own given names. The priest, who had them well studied, didn’t lose his patience over that. He unleashed four insults and half a dozen Latin words on them, and then said calmly: “But it’s my fault, because I insist on beating the tree, knowing that it can only yield acorns. The least of you has been attending this house for two months… For what, holy name of God!… And why, Virgin Mary of Mercy!… Because Father Apolinar is a real coward. Father Polinar, this son is, beside himself, a beast; Father Polinar, this other one is a mountain goat… Father Polinar, this damned creature is draining my life with every ounce of trouble; I can’t take care of him; at school they don’t pay him a damn attention for nothing… this one, that one, up above, down below; that you who understand and for that you were born… that you teach him, that you tame him, that you unlearn him… And three that are offered to me and four that I seek, taste the house full of boys; and bear their stench, and explain and pound… and bait them so that they return the next day, because I know what would happen otherwise… and do it all willingly, because that is your obligation, since you are what you are, _sacerdos Domini nostri Jesuchristi_, for which reason I say with Him: _sinite pueros venire ad me_; Let the children come to me… and laugh at the neighbor downstairs, and at this one’s father, and at the mother of the one over there, who murmur and run around and say that if you leave my hands more like donkeys than you came to them, like many others who came to me before you… _Linguae corruptae_, miserable and concupiscent flesh!… Laugh at that, as I laugh, because I must laugh… But you, cork oaks, more than cork oaks, what are you doing to correspond to Father Apolinar’s efforts? How are we doing with our primer after two months?… Neither the O, horn, nor the O is recognized in these classrooms if I paint it on the wall! Well, as for Christian doctrine, it’s clear… And since I don’t want to get angry, although there were reasons to throw you one by one out of the balcony… let’s move on to something else, and praise God _per omnia sæcula sæculorum_, for the rest is nonsense. After this outburst, Friar Apolinar went on, without ceasing to walk, almost in a circle, with his hands crossed behind his back, to what he called the plain and everyday: to ask the scoundrels the most usual and simple prayers, so that they wouldn’t forget them; the only thing that He had managed to get them into their heads, though not well or completely. Muergo only needed to be tugged on three times in the Ave Maria; Cole said the Our Father exactly, and the one who knew the Creed best, among them all, didn’t go beyond “his only Son” without a prompter. In view of which, Friar Apolinar gave Sula only half a sweet biscuit; a button from the provincial of Laredo to Toletes, and a fig to Guarín. “A hair’s breadth from the wolf, children,” the poor exclaustrated man told them immediately ; “another time it will be less… and worse. And now… hospa, scoundrel!… But wait a bit, Muergo.” The boys, who were already preparing to leave, stopped. And the friar said to Muergo, lifting up the lintel of his jacket: “This can’t go on like this. Without a shirt, when there’s a jacket, go with God.” but without pants… Where have yours gone? “My mother put them out to dry in the Fig Trees the day before yesterday,” Muergo stumbled. “And they haven’t dried yet, man of God? ” “A cow gnawed them while my mother was gutting a hake that was killing her. ” “Punishment from God, Muergo; punishment from God!” said Friar Apolinar, scratching his neck. “Hake that smells bad because it’s rotten is thrown into the sea, and it’s not cleaned far from the people to be sold later, at half price, to poor people like me, who have good gullets. But nothing remains of the pants, man? ” “The ass,” Muergo responded, “and that one, _in a gang_.” “It’s not much,” replied the ex-cloistered man, turning inside his clothes, a movement that was very habitual with him. “And there are no others in the house? ” “No, sir. ” “Nor a hint of where they might come from? ” “No, sir. ” “Horn with the fennel!… Well, you can’t go on like this, because even if you have plenty of cloth to wrap yourself up, the halyard might break; you don’t notice it, and if you do, it’s all the same to you… So it’s the same old thing, son, the same old thing: you, who can’t, carry me on your back, Father Apolinar. Isn’t that it? Isn’t it the purest truth? Horn it is!” Muergo shrugged his shoulders, and Brother Apolinar went into the bedroom. He could be heard pushing inside and muttering some Latin phrases under his breath; and he was not long in appearing, raising the curtain, with a black bundle in his hands, which he immediately placed in Muergo’s. “They’re nothing much,” he said to him; “but, after all, they’re breeches. Tell your mother to mend them as best she can, and not to let them dry in the Higueras when she has to wash them; and if they still seem too few to her, let her console herself with the knowledge that at the present time he has no better ones, nor as many as you, Father Apolinar… So, turn, you scoundrel, forward!” Once again the crowd was in turmoil, grunting and snorting like a herd of pigs sniffing the kitchen as they leave the pigsty. Every grungy countenance showed a desire to reach the stairs to examine Brother Apolinar’s gift, which still retained the warmth that had struck Muergo when the poor ex-cloistered man had handed it to him. When the door opened, two new figures appeared in the room. One was a fresh-faced, plump youth with black eyes, abundant, lustrous, and unruly hair, a smiling mouth, a round chin, and teeth the color of bronze health. He looked about twelve years old and was dressed like the children of “the lords.” He was holding by the hand a poor girl, much shorter than he, thin, pale, somewhat aquiline, with hair bordering on blond, with a firm brow and a bold gaze. She was barefoot, and wore nothing over her white, clean flesh, as far as it was exposed, but a short, old serge petticoat, tied around her supple waist over a shift worn thin by use, but neither torn nor greasy, qualities that were also evident in the petticoat. There are creatures who are necessarily clean without realizing it, just as cats are. And the comparison should not be considered inappropriate, for there was something of this little animal in the graceful lines, in the soft, sure footing, and in the suspicious and unfriendly demeanor of the young girl. As soon as Muergo saw her, he burst out laughing like a fool; Cole let out a big curse, and Sula a medium one. The newcomer imitated Muergo with a fake laugh, putting on a very ugly face, paying no attention to the other two scoundrels, nor to Father Apolinar himself, who lit a flirtatious blow at each of the three. “What’s with all this laughter, beast, and these filthy swear words, you swine?” said the friar as he slapped the head. “It’s the altera… ha, ha, ha!” replied Muergo, scratching the back of his neck, which had been bruised by Brother Apolinar’s knuckles. “We know it,” explained Cole, feeling his hairy hair. “There’s not much at stake, if it weren’t for Muergo,” added Sula. Muergo laughed stupidly again, and the girl mocked him again . “And that’s why you’re laughing, goose?” said the friar, throwing another flirtatious jab at her. “Well, the whole deal is laughable! ” “It’s a dirty street,” repeated Cole, “and she was making a barquín barcón on a perch that was floating in the Maruca… Sula and I were there throwing stones at her from the shore. Then Muergo came along… hit her with a log, and she went headfirst into the water. ” “Who?” asked the friar. “She,” replied Cole. “I thought she was playing for it, because she was sinking…” And Muergo was laughing. “And I,” Sula jumped up, “said to him: ‘Chapla, Muergo, you who swim well, and pull her out, because she’s taking a risk!'” And then he jumped into the water and pulled her out. Afterwards, we put her keel up; and with blows on her back, she spewed out the water she had taken in. ” “Is that true, girl?” the ex-cloistered man asked her. “Yes, sir,” replied the one she had addressed, still imitating Muergo, who laughed like an idiot again. “Common,” said the ex-cloistered man. “But why have you come here, and why have you come, Andresillo, and why are you holding her by the hand? In what tavern did you eat together, and what kind of whistle am I going to play in these adventures? ” “It’s a back street,” replied the one called Andresillo very seriously. “I’m starting to find out, damn it!” “I’ve been told this three times already. And what’s the point? ” “I know her from Muelle Anaos,” continued Andrés. “She goes down there almost every day.” “I didn’t know about La Maruca… but I do!” he gave Muergo a sour little gesture, because I know these guys too. “From Muelle Anaos?” asked Friar Apolinar, without a hint of surprise. “Yes, sir,” replied Andrés. “They go there quite often. ” “And he goes to La Maruca,” added Guarín. “Fuck the boy, and what a fortune he gets! But let’s get to the point. It turns out, so far, that this girl is a street urchin, and that you and this rascal, despite your respective names, are… made for each other … And what else?” –That this morning the _talayero_ told my mother that the _Montañesa_ was in sight… and I left home to go to San Martín to see her come in… and I arrived at the Anaos Dock. –To the Anaos Dock!… Don’t you live on San Francisco Street now? –Yes, sir. –Well, you were on the right path to go to San Martín! –I was going to see if _Cuco_ was there and he wanted to accompany me. –Cuco! Are you also a friend of Cuco, that rude, impolite coarse fellow , who sings me indecent songs as soon as he sees me from afar?… The hell with the kid! –I never hear him say such things… He’s bad, he is a bit bad; but he doesn’t hurt anyone. He goes in Castrejo’s boat, and teaches me to row, and to throw cabbages and tapas, and to rest on my back and standing up… “Yes, and to steal your father’s cigars to give them to him; and to run school, and to go to war… and many other things that I’m not going to mention… Well, your father would be in a good mood if, when he came in today with the corvette, he saw you on the San Martín rocks in the company of such an illustrious comrade! Horn, I remember the fennel!” Andrés turned very red, and said, with his head slightly bowed: “No, sir… I don’t do any of that, Pae Polinar. ” “What do you mean by that, you’re going to confess to me now?” replied the friar with great sarcasm. “But what do I care about those things, Andresillo?… Anyway, we’ll talk about this on a better occasion.” Now, get on with the story. What “Did Cuco tell you at the Anaos Dock ?” “I didn’t see Cuco because he was working as a freighter with some gentlemen. But she was eating a piece of bread that some calafates had given her, out of pure pity, and she told me that she had slept last night in a boat because she had been thrown out of the house. ” “And why? ” “Because she really likes to be a rascal, and they beat her. ” “Beautifully, damn! That’s what you call a hell of a school for a woman! What’s your name, daughter? ” “My name is Silda,” the one addressed responded dryly. “She’s from the backstreet,” added Andrés. “Go on, and that makes four!” exclaimed the priest. “I don’t have a father… ha, ha, ha!” croaked the wild Muergo. The girl imitated him, as usual. “She gambled away her life in San Pedro del Mar during the last sea bream season,” Cole said. “She doesn’t even have a mother,” Sula added. “A street vendor named Uncle Mocejón took her in out of pity,” Andrés explained. “Ta, ta, ta, ta!…” Father Apolinar exclaimed upon hearing this. “So this girl is the daughter of the late Mules, a widower for two years when he died this winter, with those other unfortunates… Well, I took only a few steps, by the grace of the Virgin, for them to take you in at that house!… My child, I didn’t know you before. It’s true that I don’t remember having seen you more than twice, and those times badly, as I see everything with these mischievous eyes that don’t want to be good… Common; but what’s it about now, Sir Andrés?” “Well,” he replied, turning the cap over in his hands, “I told her, when I heard what she told me, ‘go back home.’ And she said to me, ‘If I go back they’ll break my back; and that’s why I don’t want to go back. ‘ And I said, ‘What are you going to do here alone?’ And she said, ‘What others do.’ And I said, ‘Perhaps they won’t hit you.’ And she said, ‘They’ve hit me many times… everyone is bad there, and that’s why I ran away never to return.’ And then I remembered you, and I said to her, ‘I’ll take you to a man who will arrange everything, if you want to come with me.’ And she said, ‘Well, let’s go.’ And that’s why I brought her here. All this while the girl, when she wasn’t making gestures to Muergo, was scanning the floor, the furniture, and the walls with her eyes, as serene and calm as if she had nothing to do with what was being discussed there between Father Apolinar and the son of the captain of the _Montañesa_. “That is to say,” exclaimed the blessed friar, crossing his arms in front of his protector and his ward, “that there were only a few of us, and my grandmother gave birth. Damn the bargains Father Apolinar gets! Let families be untied; let marriages be untied; let children escape from their homes; let the two Town Councils be torn to pieces; Let Juan fall in love with Petra without panties with a lot of cherry… let Cabarga’s beak sink and the mouth of the port close… here’s Father Apolinar who fixes everything, as if Father Apolinar had nothing else to do but straighten what others twist, and untangle beasts like those who listen to me. And who told you, Andresillo, that it’s enough for me to want this girl to be taken in by a respectable house, to consider her taken in already? And how do you know if, even if that were possible, I would want to do it? Didn’t I do it once already? Has it served any purpose? Have they even thanked me? Well, you know that other people’s business kills the soul; and I am occupied with other people’s affairs up to the crown, up to the crown, son… and higher too!… A horn with the fennel of my sins!… Here the friar turned twice around the room, while the eight children looked at one another, or some of them stretched, or most of them grew bored; and after writhing twice in succession inside his garment, he stopped before Silda and Andresillo, and said to them: “So what you want is for me to accompany you right now to Mocejón’s house, and speak to his soul and tell him: here is the prodigal son who returns repentant to his paternal home… ” “Not me,” Andrés interrupted briskly; “this is the one you must accompany. I am going right now to San Martín to see my father come in, for he must be here by now if he knocks or arrives.” “And I’m going with you,” said Silda with the greatest freshness. “I like it.” “It’s a great trouble to see those big ships come in…” “Then, you devil of a goat,” retorted Friar Apolinar, standing to attention before her, “who am I going to work for? What am I going to pocket with this bad luck? If you don’t care what comes of the step you’re forcing me to take, what the hell should it matter to me? Well, I’m not going, come on! ” “Yes, Pa Polinar,” said Andrés, looking at him very smilingly. “No, no!” replied the friar, wanting to be inexorable. “Yes, yes,” insisted Andrés. “Horn!” replied the other, almost enraged, “I’ll bet both ears that it won’t, and I’ll bet it won’t!” Then, as if the eight figures surrounding him had instantly agreed , they shouted in unison, at the top of their voices: “Yes indeed!” And when they saw the friar nervously scratch his head and butt his head at Muergo, they all rushed en masse to the stairs, which, narrow and worm-eaten, trembled and creaked, and they didn’t stop until they reached the doorway, where Father Apolinar’s gift was examined. After everyone had agreed that it was nothing special, Andrés said to Silda: “By the time we return from San Martín, Polinar will have been to Uncle Mocejón’s house, or somewhere else… I’ll jump up and ask him what’s happened. You wait for me here, and I’ll come down and tell you. Don’t worry, we’ll all sort it out together. Now, let’s go.” The girl shrugged, and Muergo, tightening the knot of his coat’s halyard, said through bared teeth and rolling his eyes, “I’m going too, as soon as I drop these pants off for my mother. ” “And me too,” added Sula. Silda called Muergo a donkey; Guarín, Cole, and the others said they were going, some to the Anaos Dock, some to the boats, some to other chores, and Muergo to drop off his pants at home, and they set off briskly. All this happened on a beautiful June morning, many years… many years ago, in a house on Calle de la Mar in Santander; in that Santander without breakwaters or extensions; without railroads or urban trams; without the Plaza de Velarde and without stained-glass windows in the cathedral cloisters; without hotels in Sardinero and without fairs or barracks in the Second Alameda; in Santander with a dock and with boats up to the Fish Market; the Santander of the Anaos Pier and the Maruca; that of the Holy Fountain and the Cave of Uncle Cirilo; that of the Huerta de los Frailes in the open valley, and of the provincial of Burgos growing old in the San Francisco barracks ; that of the Botín house, inaccessible, alone, and uninhabited; that of the Martyrs in La Puntida, and of Tumbatres Street ; that of the giant girls on November 3rd, the anniversary of the Battle of Vargas, with luminaries and fireworks at night, and of the bullfights in which Chabiri killed, Zapaterillo gored, Rechina placed banderillas, and Pitorro fought cape-fights, in the Botín square, with music from the Nationalists; the Santander of the Inns of Santa Clara, of the Public Peso and of Mingo, the Zulema and Tumbanavíos; of the Chacolí of the Atalaya, and of the Reganche barracks on Burgos Street; of the Hormaeche inn, and of the Casa del Navío; the Santander of those decent but poorly dressed boys who, still with down on their faces, used to play skip in the Plaza Vieja, and today are beginning to bow their heads to the weight of gray hair, the work, as much as of the years, of nostalgia for venerable things that are gone, never to return; of the Santander that I have here inside, deep inside, in the depths of my heart, and carved in my memory in such a way that, with my eyes closed, I would dare to trace it with its entire perimeter, and its streets, and the color of its stones, and the number, and the names, and even the faces of its inhabitants; of that Santander, in short, which at the same time is a source of terror and mockery for the scattered and versatile youth of today, who know him by hearsay, is the only refuge left to art when with its resources it is intended to offer to the consideration of other generations something picturesque, without ceasing to to be pure-blooded, in this _pejina_ race that is disappearing amidst the motley and insipid confusion of modern customs. Chapter 2. FROM LA MARUCA TO SAN MARTÍN. La Maruca was tempting when the four boys on their way to San Martín passed by her . Water was gushing out of the gap at the back of the pier, and streams of foam marked the rising tide on the wall of the Cañadío causeway and on the beach on the opposite side, closed by the facade of a warehouse that still exists, and a high, thick wall that joined it to the east, a space occupied today by the Casa de los Jardines and the Plaza del Cuadro, with all the buildings and streets that follow them to the north, as far as the wall of the Rábago orchard. This was the Maruca in those days, connected to the bay by the culvert that emptied into the point of the Muelle, a fearful cave that very few brave souls had dared to explore, riding on a floating log. Cuco claimed to have undertaken this enterprise; that is, entering through the Maruca gap and exiting through the Muelle gap, at mid-tide; but he told such stories of thick darkness, frightful noises, rats like goats, and pitiful wails, like those of souls in distress, that they have made me doubt later that the feat was true. Many people stuck their heads into the dark mystery, but without opening their eyes so as not to see horrors, and I was one of them; but as for Cuco… bah! Why didn’t he cite witnesses when he affirmed it? And it was well worth the effort to take credit for such an undertaking, for it was the only one that could, if not be compared, come close to another, so terrifying in itself that not even a single boy dared to say he had attempted it in jest: to take no more than four steps into the mysterious cavern that led to the abyss at the bottom of which floated the stone ship in which the heads of their patron saints, the martyrs of Calahorra, Saint Emeterio and Saint Celedonio, had come to Santander; a cavern whose low, narrow entrance , stained with all kinds of filth and always closed, was contemplated with grave suspicion by both children and adults on the wall of Cristo, near San Felipe, as they passed through the vaulted Calle de los Azogues. According to popular belief, for a person to enter there was the same as to be beaten to pieces and disappear from the world forever. There had been cases, and no one questioned them, although there wasn’t all the clarity one might have desired regarding the “who” and “when.” I repeat, the Maruca was tempting for the four boys walking toward San Martín. The tide was more than two-thirds full and “live” at the time, and all the timbers were floating; and besides the usual perches, because there were always some there, two beams that hadn’t been there the day before: two beams tied together, tied one to the other and anchored with a harpoon, near the edge of the cliff. “No big deal!” as Andrés said, snorting with pleasure as soon as he saw them; “take off my shoes, roll up my trouser legs to my thighs, and with a word of “Jesus,” pull the beams a little closer, hauling on the harpoon’s end.” jump on top of them, and with the pole I have hidden somewhere close by… Damn, what a beautiful ship!… and