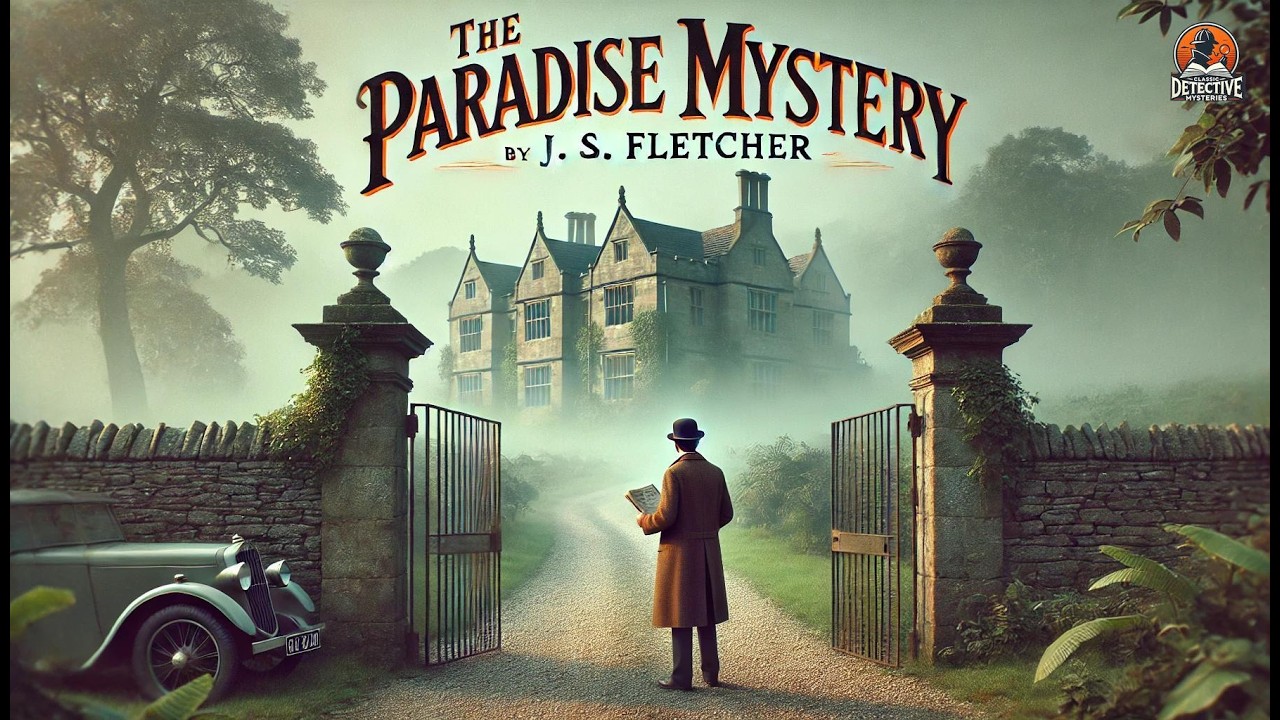

The Paradise Mystery 🕵️♂️🌴 | A Thrilling Detective Story by J. S. Fletcher