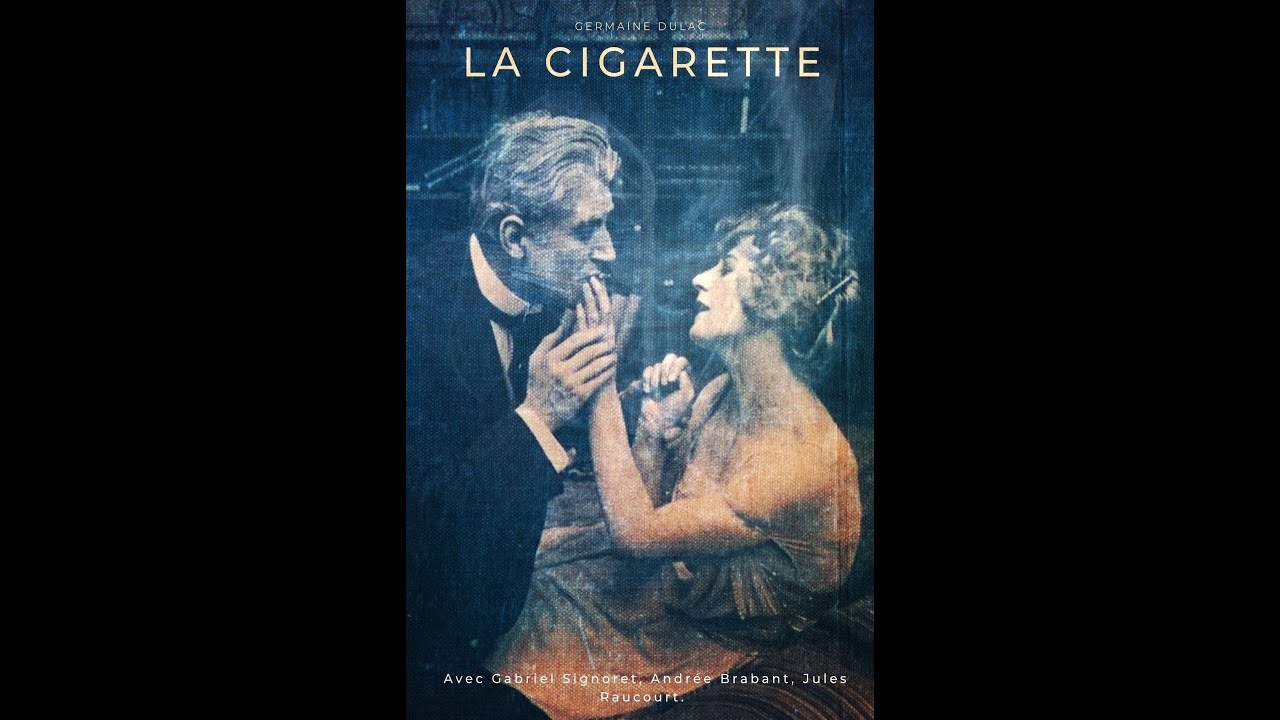

Pierre Guérande (Gabriel Signoret) is an archeologist working on a new display of the mummy of a young Egyptian Princess in a Paris Museum, and researching ancient tales of the Egyptian Princess’ tragic death.

Pierre is worried about his relationship with his pretty, and much younger wife, Denise (Andrée Brabant). He suspects Denise has lost interest in him and is cheating on him.

The older husband is very busy with his Egyptian relics, and doesn’t find time to spend with his younger wife, though the scenes with them together tend to show great affection between the two.

Denise wanders around the house and grounds after being rebuffed by her distracted husband, which leads her to amuse herself outside of the house. She is flirted with by a young and handsome, Maurice Herbert (Jules Raucourt), whose twin professions are dancing and golf. Maurice is closer to her age, but it never goes any further. However, her husband does find enough time to follow her around and he sees something that he mistook as what appeared to be a clandestine meeting between his wife and the golfer.

Pierre is a curator of ancient Egyptian artifacts, and he sees parallels between the relationship of Denise and her new Golf Instructor, and the history of the mummy he has just received. After finding out that his young wife was having an affair with a younger man, the Egyptian Princess’s aging husband grew jealous and had her killed with a poisoned seedcake.

In his resignation regarding his marriage, Pierre welcomes death as a relief and a release.

So, Pierre decides to poison one of his cigarettes and leave it up to fate to determine when he will draw the fatal one that will free his beloved wife from their marriage. He poisons a cigarette, puts it in the box on his desk, and writes a note to be discovered after he uses it at random. Thus, allowing chance to decide the moment of his death.

Throughout the film as we attempt to track the lethal cigarette, death remains a taunting menace. Ultimately, love defeats death in a surprising and uplifting ending.

A 1919 French silent drama film (a/k/a “La Cigarette”) directed by Germaine Dulac, written by Jacques de Baroncelli (as Jacques de Javon), cinematography by Louis Chaix, starring Andrée Brabant, Gabriel Signoret, Jules Raucourt, and Genevieve Williams.

The earliest surviving film by prolific pioneering feminist filmmaker Germaine Dulac. With a strong script by Jacques de Baroncelli, the film is a tale of relationship drama, jealousy, and paranoia. It’s a beautiful film with lovely costumes by Jeanne Margaine-Lacroix and impressive cinematography by Louis Chaix. It’s also an early work of cinematic Impressionism, a movement within which Dulac was pivotal. But what is perhaps most notable is how it remains engaging to a modern audience in a way that many silent films struggle to do.

Germaine Dulac (1882–1942) was a French filmmaker, film theorist, journalist and critic. She was born in Amiens and moved to Paris in early childhood. A few years after her marriage she embarked on a journalistic career in a feminist magazine, and later became interested in film. With the help of her husband and friend she founded a film company and directed a few commercial works before slowly moving into Impressionist and Surrealist territory. Before her filmmaking career, Dulac wrote articles for the feminist magazine, La Fronde, from 1900 to 1913. In 1909, she began writing for La Française as a journalist, then later as an editor until 1913. Here she interviewed a plethora of established women in France with the intention of solidifying women’s roles in French society and politics. Dulac became interested in film in 1914 through her friend, actress Stacia Napierkowska. Dulac and writer Irène Hillel-Erlanger founded D.H. Films, with financial support provided by Dulac’s husband. The company produced several films between 1915 and 1920, all directed by Dulac and written by Hillel-Erlanger, including “Les Sœurs ennemies” (1916), Dulac’s first film. Dulac and her husband divorced in 1920. After that, she began a relationship with Marie-Anne Colson-Malleville that lasted until the end of her life. She is best known today for her Impressionist film, “La Souriante Madame Beudet”/”The Smiling Madam Beudet” (1923), and her Surrealist experiment, “La Coquille et le Clergyman”/”The Seashell and the Clergyman” (1928). In 1929, she was awarded the Legion of Honor in recognition of her contributions to the film industry in France. With the advent of sound film, Dulac’s filmmaking career shifted. From 1930, Dulac returned to commercial work, and spent the last decade of her life producing newsreels for Pathé and later for Gaumont.

Like no few other surviving silent films, this one isn’t without its wear and tear, but its gender politics and relationship drama hold up surprisingly well for a modern audience. With an engrossing story, excellent direction and naturalistic performances, it’s a treat to watch.

4 Comments

Fascinating.

Awesome 👍👍🙂❗️

thanks for this and your writeup

Strange little Film…..