Editor’s Note: In honor of Tiger Woods’ 50th birthday on Dec. 30, 2025, Golf Digest is analyzing different parts of Woods’ game and career to explain what made the 15-time major champion so great. Other parts of this series will examine Woods’ putting, his fitness routine, course strategy, golf swing, equipment, and more.

One of the most important moments of Tiger Woods’ career is also one of the most misunderstood. It goes like this:

Advertisement

Only weeks after winning the 1997 Masters by 12 shots, Woods decided to rebuild his swing because he thought he could get even better.

Technically, this is true. The two-year swing overhaul under the supervision of coach Butch Harmon led to the greatest stretch of golf in history. Between August 1999 and June 2002, Woods won 7 of 11 majors, as close to golf perfection as anyone has ever come.

But this is the part people get wrong. Woods wasn’t in pursuit of perfection when he decided to change his swing, and it wasn’t because he sought to win majors by more than 12 shots. That he ended up winning the U.S. Open by 15 shots in 2000 was never the goal.

Instead, Woods’ definition of improvement was about greater consistency and less variability. It was a concession to a reality even he couldn’t avoid, because watching the tape of his Masters win weeks later, Woods saw deficiencies he sensed would be exposed.

Advertisement

“I didn’t see one flaw. I saw about 10,” Woods wrote of reviewing his performance in his book, How I Play Golf. “I had struck the ball great that week, but by my standard, I felt I had gotten away with murder. From a ball-striking standpoint, I was playing better than I knew how.”

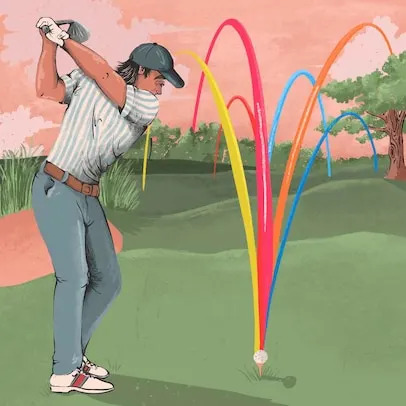

The story of a player dominating a major and determining his swing wasn’t good enough might feel like the ultimate in first-world golfer problems, but it reflects a calculation the rest of us don’t make nearly enough. The genius of Woods’ swing overhaul is it wasn’t focused on his best shots, but in elevating the quality of the bad ones.

“At that time I still thought I had good hands and I could time it up,” Woods explained decades later. “But the problem is timing that golf swing at that particular time, I’m going to hit some serious foul balls, too, and I need to get the foul balls in the position where I can play and compete, and give myself a chance every single time I teed it up. I didn’t feel like I could do that.”

Harmon said the specific changes Woods made were so subtle, most people wouldn’t recognize them, but they were significant enough for Woods to struggle through 1998, winning just once. They were also instructive to the average golfer because of how Woods filtered competition through two psychological concepts.

Advertisement

The first is what the Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi introduced as “flow,” an optimal state of complete focus and almost effortless execution. Without even describing his 1997 Masters that way, Woods’ assessment of his week is consistent with Csikszentmihalyi’s definition: Everything was easier, and he couldn’t even explain it.

This was the part that gave him pause, because as his performance experts note, flow isn’t something you can count on when you need it.

“When we coach to flow, what we’re doing is we’re making a promise that we’re going to attain this spiritual element of greatness that is only gonna happen five to 10 percent of the time,” the sports psychologist Bhrett McCabe said. “And so many factors must align for that, and what happens is the minute it’s not there, we start panicking. Our expectations get out of control and tension rises. And then we lose that flow state and we’re stuck with no tools to deal with the average.”

More Low Net

Low Net The mental trap every golfer falls into, and how to avoid it

Golf Digest Logo This quiz is designed to take the full picture of your golf year

Golf Digest Logo The case for shutting it down

Advertisement

Woods’ focus on his average points to another concept known as the “window of tolerance.” The theory, introduced by the psychiatrist Dr. Daniel Siegel, is a measure of how well we function in response to different stressors. Siegel’s focus originated with more serious subject matter like the lingering effects of emotional and physical trauma, but the underlying idea has been expanded to sports. The broader one’s window of tolerance, the better they’re able to regulate their emotions and execute in suboptimal states, which is what Woods sought when he embarked on his swing change. In wanting to hit the ball consistently under pressure, Woods recognized he wouldn’t always feel as in control as he felt at the Masters, but he still wanted to find a way to compete.

The two-year overhaul was arduous enough the golfer appeared to have regressed from his breakout form. Then he broke through to win the 1999 PGA Championship, and continued on a run in 2000 that will never be matched.

“He used to say, ‘I gotta be more consistent. I do it all with timing and I have great short game and so on and so forth. I want to get this to become second nature to where I can swing like this every time in any situation,’” Harmon said recently. “I wanted him to take the year and do a little bit at a time. But no, that’s not Tiger Woods. He wanted to do it all right now.”