Niamh Piercy, Associate Partner at Carter Jonas

Niamh Piercy, Associate Partner at Carter Jonas

Niamh Piercy, an Associate Partner at the London office of leading UK property consultancy and estate agent Carter Jonas, discusses how shifting national and local planning policies in the UK could turn struggling courses into sustainable new community hubs

When I look at the pressures facing golf clubs today, I see an industry working hard to adapt to circumstances that have changed faster than anyone expected. Managers and owners are balancing rising costs with fluctuating participation and doing so across large, complex estates that demand constant attention.

Operating costs have risen across the board. Staff wages, course maintenance, machinery repairs, business rates and energy bills all weigh more heavily than they did a few years ago. The post-pandemic peak in demand has begun to settle and the cost-of-living crisis has affected golf club membership renewals. It is no surprise that some clubs are now looking at their long-term options with a sense of realism rather than sentiment.

With the UK facing an acute shortage of housing, in particular affordable homes, it is inevitable that such extensive areas of land are being brought to the attention of planning policymakers. In England we need around 300,000 new homes per year, yet delivery remains far short of that figure, which puts growing pressure on local authorities and developers to find land in sustainable locations.

A significant number of golf courses across the UK are located in the Green Belt, a designation whereby we have already seen a shift in national planning policy. In acknowledgement that housing needs necessitate the release of Green Belt in certain locations, the National Planning Policy Framework was revised in December 2024 to introduce the concept of Grey Belt as an additional exemption where development might not be regarded as inappropriate.

Where a site is defined as Grey Belt, meets an identified housing need, is sustainably located, and delivers affordable housing, alongside infrastructure improvements and good quality open space in line with the ‘Golden Rules’, it should be regarded as suitable for development. For many golf courses, this creates a structured route for considering change in a way that aligns with the NPPF’s focus on making effective use of land and prioritising sustainable locations.

Planning applications for golf course redevelopment are already emerging and decisions are demonstrating how the Grey Belt framework is being applied in practice. Carter Jonas recently obtained planning permission for the redevelopment a golf club to provide over 200 new homes supported by a GP surgery, a café, play areas, a new country park designed to increase public access to green space as well as a biodiversity site. The site met the definition of Grey Belt involving the reuse of previously developed land that did not strongly contribute to Green Belt purposes and offering much needed homes in a sustainable location.

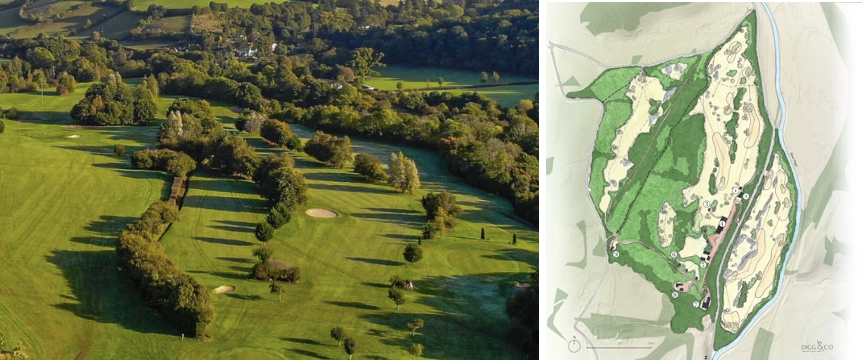

Plans to redevelop Hersham Golf Club in Surrey into a housing development with a country park were approved in March this year by Elmbridge Borough Council

Plans to redevelop Hersham Golf Club in Surrey into a housing development with a country park were approved in March this year by Elmbridge Borough Council

But the shift in planning policy does not appear to be stopping at the national level. We are also experiencing a shift at regional and local levels. The consultation document for the next London Plan accepts that some areas of Metropolitan Open Land (MOL) are not delivering the value originally intended. It points specifically to golf courses that offer limited public access and biodiversity. The suggestion is not that these sites should be released by default but that they merit assessment.

The Greater London Authority (GLA) has begun a comprehensive Green Belt Review engaging with the boroughs and other key stakeholders such as Historic England, Natural England and the Environment Agency, although it appears that a handful of boroughs remain reluctant to participate. Outside of London, local plan reviews offer another route for considering Green Belt boundaries and I expect to see more golf course sites coming forward as potential site allocations in emerging local plans over the coming years.

I think it is important to acknowledge that golf course redevelopment is not a universal answer. Many clubs remain viable and valued and should continue to thrive. However, for others, redevelopment provides an opportunity to secure financial stability. It can also deliver much needed new homes and community infrastructure in sustainable locations, biodiversity improvements by restoring habitats and creating green corridors, as well as public access to green space.

Redevelopment does not have to mean the loss of golf altogether. Some clubs may find that reducing their footprint provides a workable compromise. A shift to nine-hole layouts can improve viability and offer formats that are more accessible to new players. England Golf has set out its Golf Strategy for 2025-30 which involves lowering barriers to entry. In my view more flexible course configurations can support that ambition and create a scenario where clubs remain active and relevant while also unlocking land for homes and new community facilities.

Teign Valley Golf Club in Devon is looking to reduce its 18-hole course to 12 holes in order to provide holiday accommodation, an extended clubhouse, and padel and pickleball courts to diversify the leisure offering and protect the club’s long-term viability

Teign Valley Golf Club in Devon is looking to reduce its 18-hole course to 12 holes in order to provide holiday accommodation, an extended clubhouse, and padel and pickleball courts to diversify the leisure offering and protect the club’s long-term viability

Often when golf course are reduced in size the land freed up can be used for other sporting uses, such as football training grounds or padel courts, in recognition of other growing and inclusive sports.

I am not suggesting that all golf courses should be redeveloped. Many will continue to play a valued role in their communities. But in certain sustainable locations there is a clear case for policy-led redevelopment. Approached in the right way it becomes possible to deliver well designed neighbourhoods with strong walking and cycling connections and landscape-led layouts that can improve biodiversity.

By taking proposals through the plan-making process local planning authorities can weigh housing need alongside the importance of leisure provision and environmental considerations and reach outcomes that support both community wellbeing and long-term sustainability.