Quiet on the tee? The howler monkeys weren’t having it.

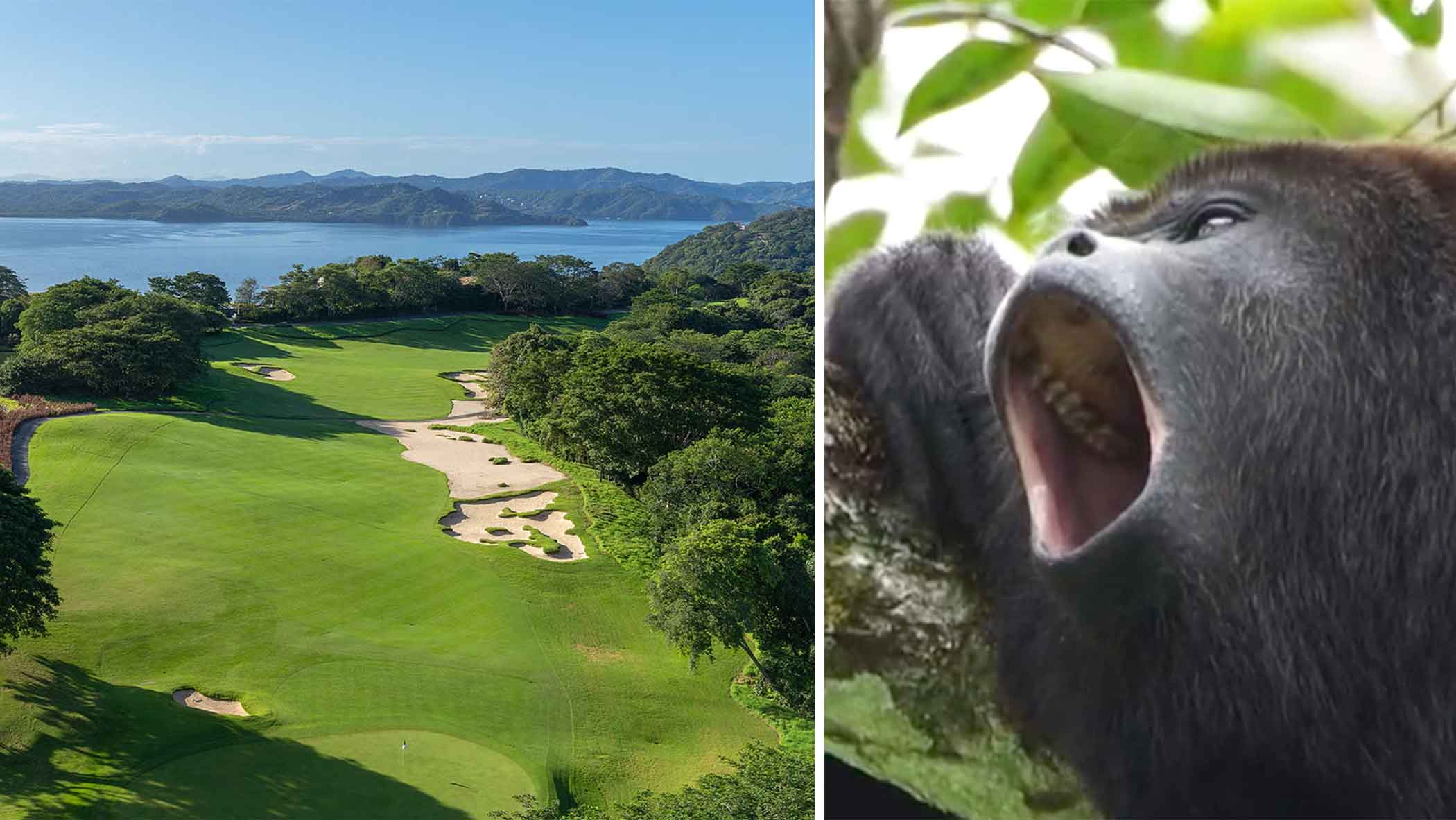

Hidden in the canopy above me, the loudest mammals on the planet were holding forth in full-throated violation of golf etiquette: primates with bad manners and a misleading name. Never mind the moniker. Howler monkeys don’t howl so much as bark and growl at a volume disproportionate to their size. Most stand shorter than your putter, but their guttural calls can be heard for miles. Think mini Chewbaccas with megaphones.

In another setting, a racket in my backswing might have been a bother. But this was what I’d hoped for when I booked a tee time in Costa Rica — a chance to play the game in close contact with nature and all its accompanying sights and sounds.

Beyond that, I wasn’t sure what to expect, because pretty much everything I knew of Costa Rica had absolutely nothing to do with golf. I doubt I was alone. For those who have never set foot in Costa Rica, the country tends to register as a Wikipedia page, replete with rain forests and reefs, waterfalls and waves, friendly locals, and an affordable outdoor lifestyle. All of it true. Little of it related to fairways and greens.

Those same features have also made the country a magnet for expats. In the mountainous inland areas and along the coast, roadside sodas — the humble, family-run cafés that serve up casado plates and fresh fruit juice — stand astride yoga studios, surf schools, and espresso bars of the kind you might stumble on in Santa Monica. That medley of the local and the imported fuels an economy that was once powered by agriculture and now runs largely on eco-tourism.

Conservationism doesn’t just help put food on Costa Rican tables. It’s also a source of national pride, supported by public policy. At roughly the size of South Carolina, the country covers about 0.03 percent of the planet’s land mass yet contains close to 5 percent of its biodiversity. Hunting for sport is not allowed. Roughly a quarter of Costa Rica has been set aside as national parks or wildlife refuges.

Golf exists, too, but in small slivers, which makes sense given the numbers. There are only about 2,000 registered golfers in a population of 5 million, and roughly a dozen courses, some of which are little more than makeshift backyard layouts. The oldest clubs, such as Costa Rica Country Club, are clustered around the capital city of San José. But for most visitors, the game unfolds on the northwest coast, around Peninsula Papagayo, where the fairways share space with jungle and ocean.

The peninsula, which overlooks a gulf of the same name, is a mosaic of steep headlands and hidden coves, with resorts stitched into the slopes. The Ocean Course at the Four Seasons snakes along coastal bluffs, its holes necklaced to showcase the views at every turn. You drive from green to tee, popping out in clearings with stunning panoramas.

The scenery comes with a cast of local characters. By the time I made the turn, the howlers’ morning chorus had died down. Near the clubhouse, though, I saw another type of monkey — a white-faced capuchin — conducting a snack raid on someone’s unattended cart. Moving through the back side, I watched two bucks, antlers locked, battling for the attention of a doe that looked on with what I could swear was slight embarrassment. An anteater scurried across a railing by the cart path — a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it apparition.

When I wasn’t on the course, I did what golfers do best between rounds: I lounged, but only long enough to reboot for other activities. The Andaz, where I was staying, offers snorkeling, paddle boarding and an eco–zip line cut through a nature preserve: a trapeze act for wannabe Tarzans. (There is more to come. Next month, Peninsula Papagayo will cut the ribbon on Papagayo Park, a lifestyle hub outfitted with a pump track, pickleball, a lap pool, a fitness platform and more, all available to guests and residents of the Andaz, the Four Seasons and Nekajui, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve). Another way to tour the treetops is via a canopy walk along wobbly planks and rope ladders. From one of those lofty vantage points, I finally got a close look at one of the cacophonous culprits I’d heard on the course: a howler monkey, reclining on a branch. My guide told me they spend most of the day nibbling fermented fruit, which leaves them relaxing in a mild perma-buzz, but not so zonked that they stay mum.

“So, they’re loud and lazy, like my kids,” I said.

Deep down, though, I was feeling jealous, not judgmental.

That evening, I savored a few cocktails myself. But by morning I was ready to peg it again. A short drive around the coast brought me to Reserva Conchal, a Robert Trent Jones Jr. design that began life as Lion’s Paw and retains a wonderful wildness. The course winds through trees, skirts lakes, and borders a mangrove forest that doubles as a wildlife corridor. Iguanas skittered across the fairways. Toucans flashed overhead.

My playing partner was the resort’s director of golf, Carlos Rojas, who got into the game caddying as a kid near the capital and never looked back. Bubbling with energy — a vivaciousness he credited to his all-carnivore diet (“No sugar, no carbs,” he said. “I’m never tired, ever”) — he struck me as the joyful embodiment of pura vida, pure life, a phrase that serves both as a salutation and a kind of national slogan. While eating almost nothing but red meat, Rojas oversees a course that’s as green as it looks: reclaimed water, 100-percent organic fertilization, composting, and even tees and ball markers made from recycled coffee grounds.

At Reserva Conchal, Carlos Rojas runs an eco-friendly operation.

Josh Sens

Golf in Costa Rica isn’t widespread, but what exists fits perfectly within the country’s ethos: small-scale, sustainable, in sync with nature.

Back at the Andaz that evening, the jungle was alive with sound again. From the terrace, I listened to the howlers calling across the canopy — a racket, yes, but oddly soothing all the same. They were still chattering at daybreak, as I meandered back to the Ocean Course for a quick round before my departure. When I found the fairway with my opening drive, I imagined that the sound coming from the trees was cheering.

I’ll take it over Baba-booey, any day.