CARNOUSTIE, SCOTLAND | Mention Carnoustie, and the first association most golfers have with this village at the mouth of the Barry Burn is as an Open Championship venue so tough it came to be called Car-nasty.

The Open is staged on the Championship Course, one of three 18-hole layouts on a desolate North Sea links that lies a mere 14 miles north of St. Andrews as the seagull flies and has hosted eight of those tournaments to date. Invariably, it produces great winners. Tommy Armour prevailed in the 1931 edition and Ben Hogan in 1953. Gary Player and Tom Watson were victors here as well, in 1968 and 1975, respectively. And Pádraig Harrington came out on top in 2007.

But Carnoustie is just as famous for derailing the quests of players to become the Champion Golfer of the Year, with no one ever crashing quite as spectacularly as Frenchman Jean van de Velde in 1999 when he lost a three-stroke lead on the final hole of regulation play – and then lost a playoff to Paul Lawrie.

“Those boys became among the best golfers in America for many years. They were the equivalent of the Mannings in professional football in the States. And from 1898 to 1936, a Smith was a favorite in the U.S. Open.” — David Mackesey, Carnoustie Golf Club historian

What is much less known, however, is the outsized role this burg of 4,000 residents at the turn of the 20th century played in the development of golf in America. That’s when more than 200 of its native sons traveled to the States to work at the golf and country clubs that were opening throughout that land and teach Americans how to play and understand the royal and ancient game. Thanks in no small part to their enthusiastic and effective tutelage – and their willingness to endure long separations from their families and friends back home while moving frequently to different jobs throughout the U.S. – the sport came to prosper in the New World.

The legacy of the immigrant pros from Carnoustie is a remarkable one. And a single family, led by John Smith and including his three sons Alex, Willie and Macdonald, stands out for the considerable contributions it made to golf’s growth and development there.

“Those boys became among the best golfers in America for many years,” said David Mackesey, the historian for the Carnoustie Golf Club, which counted all three of them as members. “They were the equivalent of the Mannings in professional football in the States. And from 1898 to 1936, a Smith was a favorite in the U.S. Open.”

The brothers were also a favorite at the top clubs in the country that were looking to meet their members’ sudden and very passionate interest in golf and help educate them about the game.

![]()

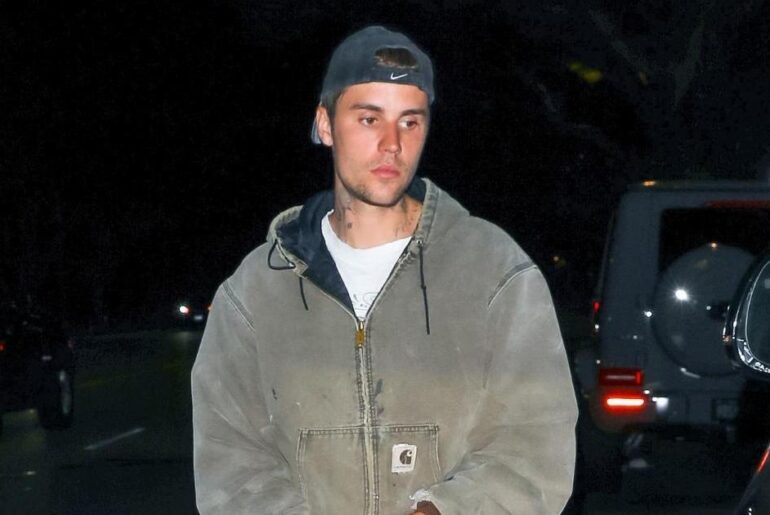

(Left to right, standing) Willie Smith, Alex Smith; (seated middle) Joann Smith, George Smith, John Smith; (seated, bottom) James Smith, Macdonald Smith Courtesy Mackesey Family Images

(Left to right, standing) Willie Smith, Alex Smith; (seated middle) Joann Smith, George Smith, John Smith; (seated, bottom) James Smith, Macdonald Smith Courtesy Mackesey Family Images

John Smith was born in 1851, and like his father before him toiled for a time in the Dundee jute mills. Jute is a natural fiber that was imported from India and used to make burlap and twine among other products. And those factories were horrid places, filled with the deafening rattle of spinning and carding machines and air so dusty that it took a worker’s breath away. Equally awful was the stench from the rancid whale oil that was used to soften the material.

Fortunately, Smith found a way out when he moved the family to nearby Carnoustie, his wife Joann’s home village, to become the keeper of the greens on its links.

Over the years, Joann gave birth to 10 children, but only five survived infancy. In time, each of those kids made their livings as golf professionals in North America, with Alex, Willie and Macdonald having the greatest successes.

As players, the trio captured three U.S. Opens as well as several Western and Metropolitan opens, which were considered major championships in those days. They won tournaments on the nascent professional circuit that would become the PGA Tour, too, and were contenders in the Open Championship.

Their presence in those events, as well as that of other overseas professionals, stirred interest in the game and lent credibility to the earliest championships in America by elevating the level of play and quality of the fields in what was still a golfing backwater.

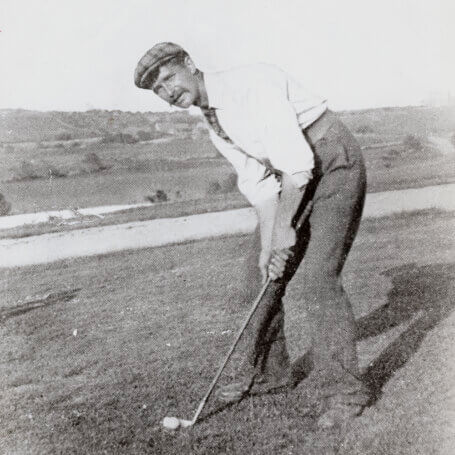

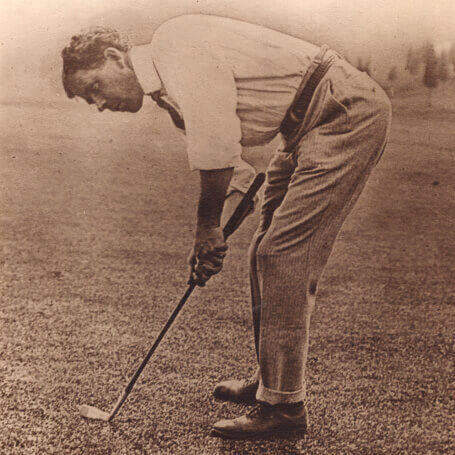

Macdonald Smith during the 1930 U.S. Open, in which he finished second to Bobby Jones. COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Macdonald Smith during the 1930 U.S. Open, in which he finished second to Bobby Jones. COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

The Smith brothers also held jobs at the most prestigious clubs on the continent, among them Shinnecock Hills, Midlothian and Oakmont, and in locales as far ranging as California, Michigan and Florida. They taught their members how to swing the clubs they made and repaired, and explained the rules of golf.

With those and other actions, they spread the gospel of golf throughout North America, introducing hundreds of newcomers to the sport as they also trained some of the best ever to play the game. Such as Jerome Travers, who captured four U.S. Amateurs; Jack Neville, a five-time California state amateur winner who co-designed the Pebble Beach Golf Links; Marion Hollins, who captured the U.S. Women’s Amateur title in 1921 before helping Alister MacKenzie create the course at the Cypress Point Club; and Glenna Collett Vare, whose playing record was so strong that she came to be known as the female Bobby Jones.

Willie Smith is even credited with almost singlehandedly nurturing the sport in Mexico even as that country – and the Mexico City Country Club for which he worked as the head golf professional – was racked by war during its tumultuous revolution.

![]()

The Barry Burn on the 17th at Carnoustie Tony Marshall, R&A via Getty Images

The Barry Burn on the 17th at Carnoustie Tony Marshall, R&A via Getty Images

Golf has been played on the links of Carnoustie since the 1500s, and records indicate that the Championship Course comprised only 10 holes when it was built in 1842 by Allan Robertson, a St. Andrean who is regarded as the game’s first golf professional. Assisting him was his young apprentice, Tom Morris. A quarter century later, Morris, who by that point had started to be called Old Tom, expanded the layout to 18 holes. Perhaps its most daunting feature was the Barry Burn, a twisting waterway that came into play at several points during the finishing holes.

Allan Robertson lies in rest at St. Andrews Barbara Ivins-Georgoudiou, GGP

Allan Robertson lies in rest at St. Andrews Barbara Ivins-Georgoudiou, GGP

That was the ground that John Smith tended in his new gig. It was also where his boys learned the game. And while he certainly nurtured their interests in golf, it was a professional named Robert Simpson who gave them the equivalent of a Ph.D. in the business.

Born in the winter of 1862 and best known as Bob, Simpson grew up just south of St. Andrews by the historic Elie links. He came from a line of successful brick masons and weavers. But the Simpsons were a golfing family as well, and at the age of 17, Bob started an apprenticeship with the local professional, George Forrester. In that position, Simpson not only learned how to play the game but also the nuances of club and ball making as well as course design and maintenance.

In time, Simpson moved to St. Andrews to work under Robert Forgan, whose well-crafted mashies, cleeks and niblicks made him the pre-eminent club maker at the time – and eventually the official clubmaker for the Prince of Wales.

Then at the age of 21, Simpson beat out 32 other applicants to become the golf professional at the Dalhousie Club in Carnoustie.

Simpson moved to that town in the summer of 1883. A few months later, his brothers Jack and Archie joined him to help open and run his shop. Both siblings were strong golfers, with Jack winning the 1884 Open Championship at Prestwick, and Archie coming in second when that tournament was played on the Old Course in St. Andrews the following year.

Bob Simpson was no slouch with a golf club, and he finished fourth in the 1885 Open, three shots behind Archie. But as the professional at Dalhousie, where the membership rolls were populated by landed gentry, jute mill owners and other denizens of the upper class, he had to focus on his members and their needs. That meant giving lessons, playing tournaments and exhibitions, and making and repairing their golf clubs. Simpson also dabbled in course design and in the mid-1890s helped Old Tom tweak the Carnoustie course he had expanded in 1867.

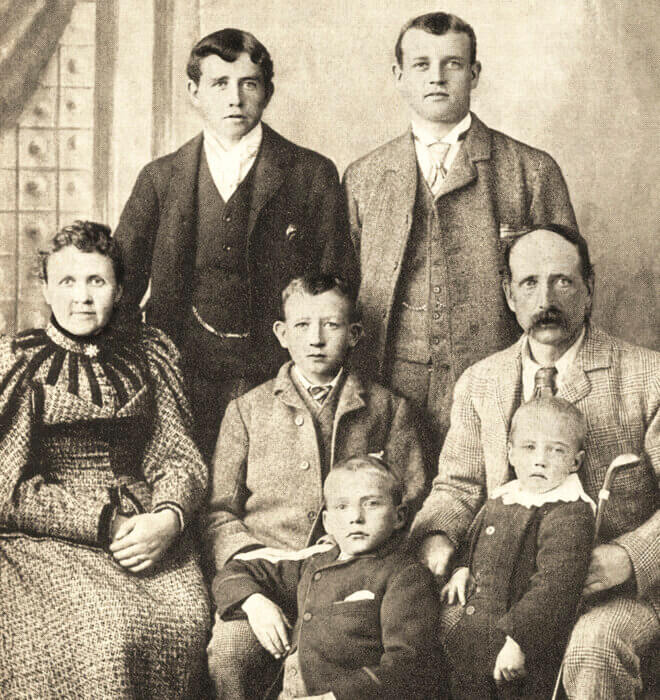

Archie Simpson during the 1902 Open Championship at St. Andrews. Among those watching is Old Tom Morris (second from left). Sarah Fabian-Baddiel, Heritage Images/Getty Images

Archie Simpson during the 1902 Open Championship at St. Andrews. Among those watching is Old Tom Morris (second from left). Sarah Fabian-Baddiel, Heritage Images/Getty Images

But as much as anything else, Simpson served as a mentor to young golfers from Carnoustie, finding work for them in his shop and teaching them all that he knew about the game and being a professional.

Mackesey says that Simpson employed as many as 30 locals at one time and frequently wrote letters of recommendation for his charges when they sought work in other parts of the golf world. “And an endorsement from Bob Simpson carried tremendous weight,” Mackesey added. In fact, it all but guaranteed that the lads would be hired.

One of those apprentices was the eldest Smith son, Alex, and in time he became the foreman in Simpson’s shop.

![]()

To many youngsters in Carnoustie back then, golf was more than a sport. It was a way out of the jute mills, which employed children as “half-timers” and promised a life of Dickensian destitution. And many of those working in Simpson’s shop hoped to find and keep good golf jobs, whether in the British Isles or far-off lands like America.

Alex was the first in his clan to travel to the States, and he did so after answering an advertisement the Washington Park Club in Chicago had placed seeking four clubmakers for the summer of 1898, with round-trip passage on a sailing ship included. Just 24 years old, he was married to Jessie Maiden, a Carnoustie native whose brothers Stewart and Jimmy would also become notable golf professionals in America, and the father of a young daughter named Fannie.

Fred Herd COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Fred Herd COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Alex applied for the position and was accepted along with three St. Andreans, one of whom was Fred Herd. They left their homeland in March of that year and returned the following November. And in addition to impressing their employer with their teaching and clubmaking skills, they demonstrated great competitive verve, with Herd winning that year’s U.S. Open, which was held at the Myopia Hunt Club north of Boston, and Smith finishing second. Not far behind, in fifth place, was his brother Willie, who had moved to America two months after Alex to become the teaching professional at Shinnecock Hills on Long Island.

Alex Smith received a warm welcome back in Carnoustie as he also learned that his wife had given birth to a second child, Margaret. But he was unable to stay for more than a couple of months because he needed to return to the States in January to accompany a group of Washington Park members on a winter golf journey to the Hotel del Coronado near San Diego, California.

Smith hated to leave Carnoustie so quickly. But it helped that his brother Willie had taken a new job as the head professional at the Midlothian Country Club in the Chicago suburbs, not far from Washington Park, where Alex would be spending another summer.

In the spring of 1899, George Smith became the third of John and Joann’s sons to relocate to America. After starting out in Chicago as an assistant to Willie at Midlothian, George went west the following year to work as a professional at the San Rafael Country Club in California. And that fall, Willie captured the U.S. Open at the Baltimore Country Club by a record 11 strokes, a margin of victory not broken until Tiger Woods took the 2000 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach by 15 shots.

Clearly, the Smith brothers had settled quite comfortably into life in the New World, and nine years after Willie’s triumph in Baltimore, they would be joined by their youngest sibling, Macdonald. Just 18 years old at the time, he would go on to win 25 PGA Tour events.

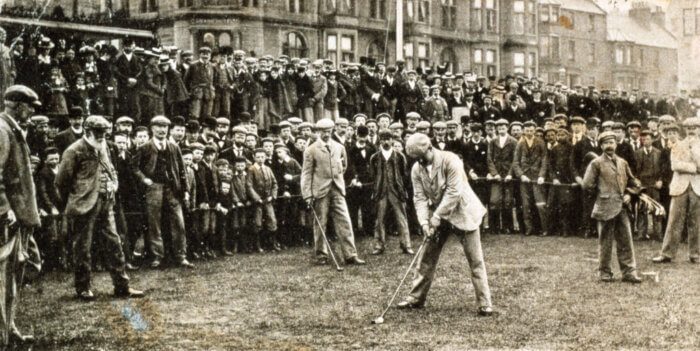

Macdonald Smith George S. Pietzcker, COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Macdonald Smith George S. Pietzcker, COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Mackesey says that Macdonald was as good as any competitive golfer in the States after he arrived. But he was never able to capture America’s national open, though he came achingly close in 1910 when he was runner-up in that tournament to brother Alex after losing to him and American John McDermott in a playoff. Twenty years later, Macdonald finished second in both the U.S. Open and Open Championship to Bobby Jones during the Georgian’s historic Grand Slam run.

In between those near-misses came perhaps the most painful loss of all, in the 1925 Open Championship, which was the last one ever played at Prestwick.

The pre-tournament favorite, Macdonald held a five-stroke lead when he teed off in the final round. But the golfer staggered home with an 82 that left him in fourth place.

In his seminal book on the golf profession, “Doctors of the Game,” PGA of America master professional Billy Dettlaff describes the gallery that day as “unmanageable,” with spectators crowding around Smith so closely that he could not put a proper swing on most shots or even see the fairways and greens in front of him. Some in the gallery were accused of kicking his balls out of good positions into bad lies to ensure that Macdonald did not win – and that they won the bets they had made against him.

Sadly, those disappointments overshadowed Macdonald’s overall playing record, which included three Western Opens titles (in 1912, 1925 and 1933) and an equal number of triumphs in the Metropolitan Open (in 1914, 1926 and 1931).

And in 1924, Macdonald finished fourth in the U.S. Open and third in the Open Championship back home.

Macdonald’s playing record was but one thing that set him apart. He also enjoyed a stellar career as a club professional, holding the head pro job at Oakmont outside Pittsburgh and serving as an assistant to his brother Alex at Wykagyl in New Rochelle, New York. Macdonald was also a pioneer in California golf, working at Diablo Country Club and Claremont Country Club in the San Francisco Bay Area, Oakmont Country Club near Los Angeles and the Del Monte Golf Course on the Monterey Peninsula.

It was during his time in the Golden State that Macdonald acted as swing doctor to Jack Neville, who captured the first of his five California State Amateur championships in 1912 and went on to represent the United States in the 1923 Walker Cup.

Jack Neville (standing with club in foreground) searches for a ball in the burn at St. Andrews during the 1923 Walker Cup. COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

Jack Neville (standing with club in foreground) searches for a ball in the burn at St. Andrews during the 1923 Walker Cup. COURTESY USGA ARCHIVES

To be sure, those jobs only moved Smith farther away from Carnoustie. But he felt quite at home in the West, especially given that his father, mother and brother James had settled in the Bay Area, with his father and James taking jobs at Diablo as well. Macdonald also worked as George’s assistant at Claremont and Del Monte.

As good a competitive golfer as Mac was, brother Alex was even better. His two U.S. Open titles, in 1906 and 1910, speak to that. So do the 11 top-10 finishes he recorded in 18 appearances in that championship. And those include being runner-up three times. Smith also took a pair of Western Open titles and four Met Opens.

But as was the case with brother Macdonald, Alex Smith stood out in other areas of the game during the 32 years he spent in the States. As a club professional, he held the head positions at some of America’s best clubs, among them Nassau Country Club on Long Island, Westchester Country Club outside New York City and the Atlanta Athletic Club, where he was the first pro. Alex also helped bring the game to such outposts as Southern California (Coronado) and Florida, where he served as the head golf professional for 20 winters at the Belleair Country Club outside Tampa before helping hotelier John McEntee Bowman establish the Miami Biltmore.

Having escaped the jute mills, Alex Smith lived a good life as a golf professional. Courtesy USGA Archives

Having escaped the jute mills, Alex Smith lived a good life as a golf professional. Courtesy USGA Archives

In addition, Alex acted as a mentor to many of the immigrant professionals who traveled from the old country to the U.S. for work, providing the same support and guidance that Bob Simpson gave him as a youngster in Carnoustie.

Alex was also much in demand in America as a teacher and counted as his pupils Jerome Travers, who in addition to his four U.S. Amateur triumphs captured the 1915 U.S. Open, and Glenna Collett Vare, the winner of six U.S. Women’s Amateurs. Not surprisingly given their records, both those golfers ended up in the World Golf Hall of Fame, as did another pupil of his, Marion Hollins.

Willie Smith had a much less peripatetic career as a golf professional, spending most of his time in the States running the golf program at Midlothian after a one-year stint at Shinnecock. But he had perhaps the most colorful one of the clan after moving south of the border in 1904 to take the head pro job at the Mexico City Country Club. Two years after that, Willie won the Mexico Open. But he continued to play in major championships, even returning to Scotland in 1910 for that year’s Open Championship at St. Andrews, finishing fifth after holding the 36-hole lead.

Willie Smith Courtesy USGA Archives

Willie Smith Courtesy USGA Archives

Things in Mexico got rather dicey with the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. At one point during that conflict, which continued through the decade, the club was occupied by troops associated with the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, as they saw it as a symbol of the corrupt ruling class. The rebels used the ballroom as a stable for their horses and stole whatever clothes the members had in their lockers.

The club remained in the crossfire for several years and was even shelled on occasion. Determined to protect the property, Smith refused to leave. Newspaper accounts reveal that during one artillery barrage, Smith hid in the cellar of the clubhouse, only to become pinned under a beam that had collapsed during the fighting.

While he survived that attack, the ongoing stress of the conflict took its toll, with Willie Smith dying the day after Christmas 1916, at the age of 40. While his body was interred in Mexico City, his brothers placed a headstone for him in the family plot back home.

That seemed an understandable move, for their home village meant the world to the Smith brothers. It may not have possessed the color and character of St. Andrews. But it had its golf. And the sport gave those brothers and many other native sons an avenue out of the jute mills and a chance to do something they truly loved. It was also a way to distinguish themselves, and they did that in large part by helping an entire country fall in love with the game at the turn of the 20th century.

![]()

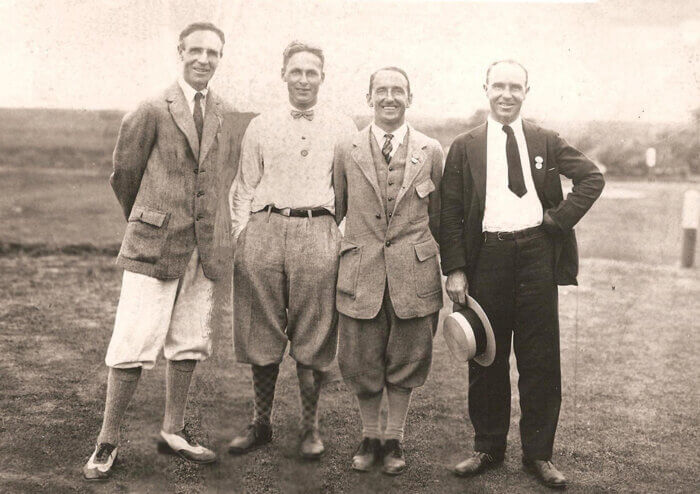

Jimmy Maiden, Bobby Jones, Bobby Cruickshank, Stewart Maiden at the 1923 Open Championship Courtesy Sid Matthew

Jimmy Maiden, Bobby Jones, Bobby Cruickshank, Stewart Maiden at the 1923 Open Championship Courtesy Sid Matthew

The Smiths certainly stood out. But others from Carnoustie made significant contributions to the growth of golf in America as well. Such as Alex’s brothers-in-law, Stewart and Jimmy Maiden, both of whom worked at East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta. Jimmy is credited with helping a young Bobby Jones get his start in golf, while Stewart served as Jones’ swing coach in later years. And it was Jimmy who gave Jones his famous Calamity Jane putter, which he used to win 10 majors from 1926 to his Grand Slam year of 1930.

Another native son of note was George Low Sr., who made his way to America after learning how to make golf clubs from Archie Simpson. He worked for some 25 years as the course superintendent and head professional at the Baltusrol Golf Club in New Jersey.

“They left home to make a living, with dreams of glory,” says Mackesey. “But like good ambassadors, they never forgot where they came from.”

Those are all things worth considering for anyone who visits Carnoustie and walks past Robert Simpson’s golf shop, which is still in business (though no longer family-owned) and where his grandson, a Grateful Dead-loving octogenarian named Trevor Williamson, stops by to talk with customers. And by the clubhouse at the Carnoustie Golf Club, where Alex, Willie and Macdonald all won club championships (and where the medals and trophies they won in their competitive careers are displayed).

Trevor Williamson and his grandfather’s golf shop are still Carnoustie fixtures. John Steinbreder, GGP

Trevor Williamson and his grandfather’s golf shop are still Carnoustie fixtures. John Steinbreder, GGP

It is also worth standing for a spell by the 18th green of the Championship Course, an easy pitch shot from both buildings, and think not only of the golfers who have won and lost Open Championships on that ground but also the people who grew up playing there and all they gave golf after bravely sailing to the New World.

There is nothing nasty about that.

Top photo: Macdonald Smith during the 1925 Open Championship (Kirby/Topical Press Agency, Getty Images)

© 2025 Global Golf Post LLC