As the PGA Tour’s fall season winds down, there’s a renewed urgency for players to earn fully exempt status. For the first time in more than 40 years, finishing among the top 125 in points (previously top 125 in money), will not be enough to guarantee full status.

The new number is 100.

It’s all been the subject of a good bit of conjecture since the changes for Tour eligibility were announced more than a year ago.

Sign Up Now. SI Golf Newsletters. Sports Illustrated’s Free Golf Newsletters. dark

Not only were the Tour exempt spots trimmed, but so, too, the number of players coming from the Korn Ferry Tour. Some Monday qualifying spots have been eliminated, too.

All in the name of a leaner, meaner PGA Tour with tidier fields.

All of which brings some chuckles among a long-ago era of PGA Tour players. Back then, exempt status was far more elusive than today’s 100 spots.

Try only 60 spots. With a Qualifying Tournament that only assured a spot in a Monday qualifying event. And exemptions for winning tournaments that didn’t necessarily last more than a year. And the knowledge that missing a cut meant going to the next tournament site and getting into the field through a Monday qualifier.

“I think it made us better players,” said two-time U.S. Open winner Andy North, who turned pro in 1972. “You were grinding on Monday to get in and then grinding on Friday to make the cut. And then if you made the cut, a top 25 meant you’d be exempt for that same tournament the following year.

“I missed the top 60 by a few hundred bucks my first year. I had like 10 top 25s for the next year. I knew I could take a week off and get back out there [because I was in those tournaments]. The exempt players could plan a schedule. But my first year, I played the first 18 tournaments in a row. I kept making cuts and you weren’t going to go home if you made it to the next week. It really toughened you up. You had to grind your butt off. I always thought that was a better way. When we went to 125, I thought the number should have been more like 90.”

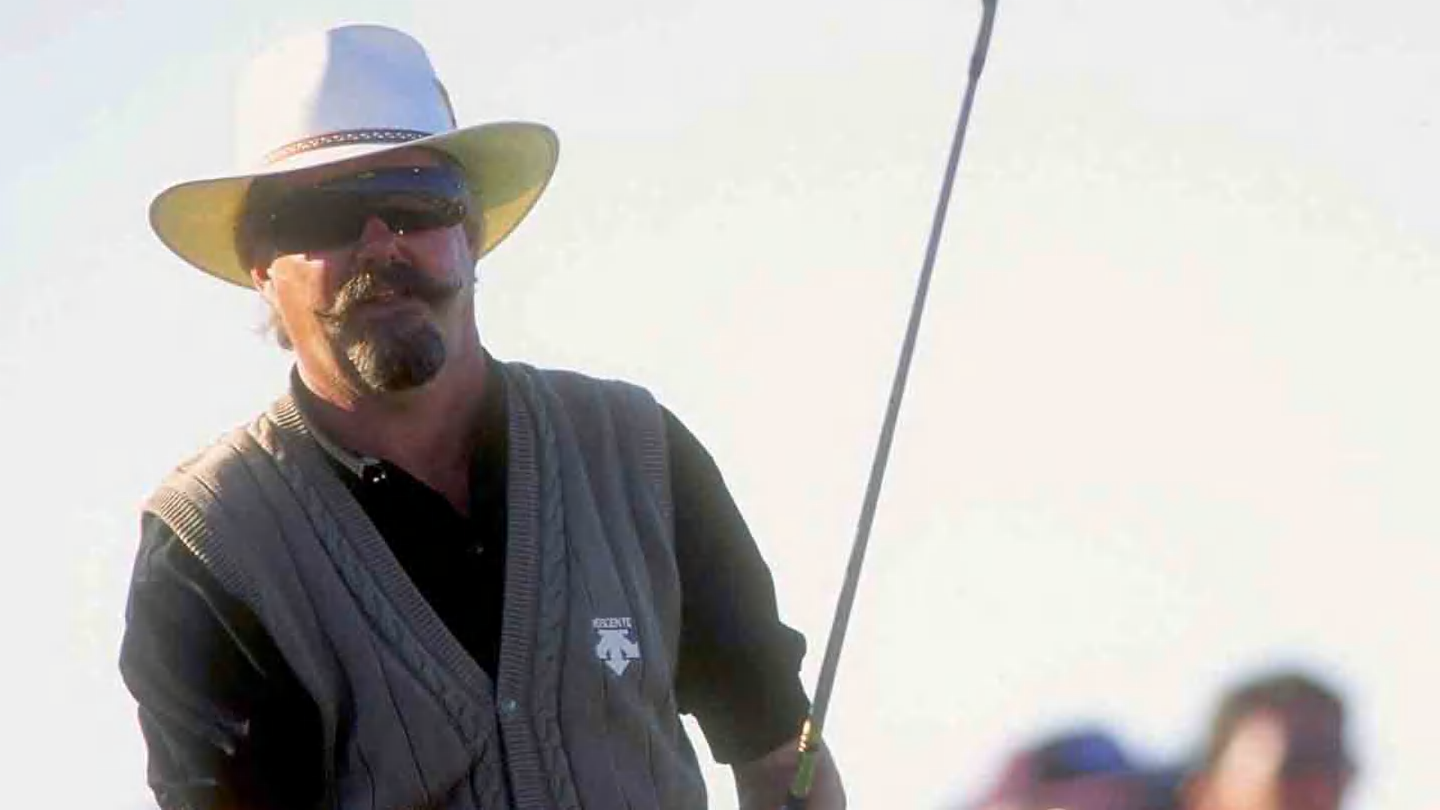

Two-time U.S. Open champion Andy North said the format of the PGA Tour of 50 years ago made for tougher players. / The Augusta Chronicle-USA TODAY NETWORK

That happened in 1983, after former Tour player and long-time broadcaster Gary McCord put together a concept called the “All-Exempt Tour.”

McCord had “earned” his way onto the PGA Tour after turning pro in 1973 by finishing second to Ben Crenshaw at the fall Qualifying Tournament. (Crenshaw would win the Texas Open that fall in his first PGA Tour event as a pro.) That didn’t give him entry into tournaments. It meant he had the ability to Monday qualify, and at the first event where he tried at the 1974 L.A. Open, he was part of 180 players in one qualifying field vying for just one spot. Another qualifier for one spot had similar numbers.

While many fields had far more spots—a lot depended on how many players finished top 25 the year prior, how many the cut the week before and how large the field was—it was still an unnerving way to go about playing competitive golf and making a living.

Anyone who was not in the top 60 of the previous year’s PGA Tour money list faced Monday qualifying. From there, making a cut or finishing top 25 was the only way to avoid Mondays—unless a player won.

McCord only made the top 60 one time in nine years. He, like many others, was a “rabbit” who went week to week never knowing if he could set a schedule. Players ran out of money chasing Mondays and McCord began toying with a better way, putting pen to paper in 1981 and eventually taking his idea to Tour leadership, including commissioner Deane Beman.

The former Tour player had been in charge since 1974 and agreed that the Monday qualifying system was not the best. In Adam Schupak’s book, Deane Beman: Golf’s Driving Force, the former commissioner said he had actually been in favor of a way that allowed for more players to be exempt.

“The system cried for a better alternative,” Beman said.

McCord’s view was more colorful: “It was an ever-evolving trip down the toilet is what it was.”

But Beman had been unable to get player buy-in. McCord’s plan finally hit and was enacted in advance of the 1983 season.

Different ideas had been floated for the number of fully exempt spots, from as few as 90 to as many as 170. They eventually compromised on the 125 number that existed until this year. “Gary deserves credit for convincing the guys that it was a better idea,” Beman said.

“Back then I think it was welcome just because of the lifestyle of a “rabbit” was pretty brutal,” said six- time PGA Tour winner Gary Koch. “It was guys jumping in a car and driving hours and hours and hours to get to the next site. The Tour then scheduled the events in a better logical geographic order which helped. But [the all-exempt tour] was very welcome.”

Koch, who like North played college golf at the University of Florida and later spent years as a TV golf analyst, turned pro in 1975 and went through the Qualifying Tournament that year at Disney World.

With just one stage of qualifying—unlike three today—there were some 600 players spread out among three courses with a cut after 54 holes.

“There were 25 guys who got cards which allowed us to go Monday qualify,” Koch recalled. “The first event I played in was in Tucson and all Class A members of the PGA of America were allowed to try and Monday qualify also. There were two courses and 120 of us on each course, with just seven spots at each available.

“I ended up in a playoff for two spots and got the last spot in the tournament. I made the cut and managed to do that in all six events I played on the West Coast and only had to go to one Monday qualifier.”

Koch got his first win the following year at the Tallahassee Open, which was an opposite-field event where many players who were not exempt for the regular tournament would show up. That victory came with a one-year exemption.

Gary Koch still felt pressure to finish among the top 60 even after his first PGA Tour win. / Getty Images

Because it didn’t carry through the following season—now a victory means exempt status for the rest of the year and the following two seasons—Koch still felt the pressure to finish among the top 60 money winners.

“It was a very different system,” Koch said. “I would argue that it made for tougher competitors than you have now from the standpoint that making the cut was such a big deal. I always found that when I was in contention, I thought it was easier because you knew you were playing well. But hovering around the cut line you don’t have your best stuff. You’re grinding away because making the cut was so very important.

“You don’t have to jump in your car on Saturday morning and drive to wherever the next tournament was for Monday. Maybe get in a practice round on Sunday if you were fortunate and then play on Monday. It was a hard existence. But it made for tough competitors because you had to perform.”

Back then, there was no Korn Ferry Tour, which is a developmental circuit where players can hone their skills, earn money and ascend to the PGA Tour. That tour’s top 20—down from 25—now are exempt on the PGA Tour the following year. There was also not a developmental tour such as the PGA Tour Americas nor the proliferation of mini tours that exist today.

“There was something to play for all the time,” said two-time U.S. Open champion Curtis Strange, who turned pro in 1976 and went on to win 17 times on the PGA Tour. “If you were 40th place going into Sunday and you shot 65 or 66 you got into the top 25 and that was a feather in your cap for the next year.

“That’s why when you talk about no cuts … it’s such a staple of the Tour and for our leadership to change that and think that’s O.K. [referring to the signature events] … I just don’t think it’s right. Back then, I would make cuts but also go to numerous Monday qualifiers.

“Sometimes there were only four or five spots. You played hard and it was a lot of pressure. That was the job for the week.”

So while there is understandable concern about the Tour’s new changes, players had it much tougher prior to 1983.

Two-time U.S. Open champion Curtis Strange takes issue with the addition of no-cut events on the PGA Tour. / The Augusta Chronicle-USA TODAY NETWORK

The difference, of course, is that today’s world of golf is far more competitive. Taking away 25 fully exempt spots is jarring, as is removing five spots from the Korn Ferry, down to 20 from 25. That’s 30 lost positions. Q-School is now only five spots when far more players used to advance via that avenue.

“I just think there are more than 100 guys capable of playing the PGA Tour,” said 12-time winner John Cook, who also began his career under the old system.

The good news is that unlike previous years, players who are fully exempt via the Korn Ferry Tour and Q-School are all but assured of spots in every full field regular PGA Tour event, aside from perhaps the WM Phoenix Open.

That is 19 tournaments during the regular season, with the potential to qualify for signature events. Plus, there is the FedEx Fall schedule, which appears to provide a minimum of seven starts. The tournaments being contested now have few of the top players in the points standings, meaning more opportunity.

“I can see both sides of the argument,” Koch said. “I understand from what you would call the rank-and-file players of the Tour. The membership feeling that playing opportunities are being taken away. The system has been in place since 1983. And change is often not viewed upon very kindly by some.

“That being said, I think it will enhance the product. I know the slow play that has been written a lot about and this is meant to speed up play [with smaller fields] and get guys around. And that will obviously be a benefit. I also think it will potentially force players to play more. The mindset [previously] is just go for broke all the time, and if you don’t do well, you can play next week. But those points are now reduced and it might produce a different mindset

“You used to have a number of players who seemed to finish in the top 100 to 125 year after year. The argument to me then becomes, ‘Would a younger, new player play better?’

For those players on either side of that bubble, there is no time to fret about it now.