This content will appear in the next issue of Golf Journal, a quarterly print publication exclusively for USGA Members. To be among the first to receive Golf Journal and to learn how you can ensure a strong future for the game, become a USGA Member today!

A few months shy of his 90th birthday, Gary Player walks through the clubhouse of Aronimink Golf Club, the historic club outside Philadelphia where he won the PGA Championship 63 years earlier, on his way to work out before his afternoon tee time.

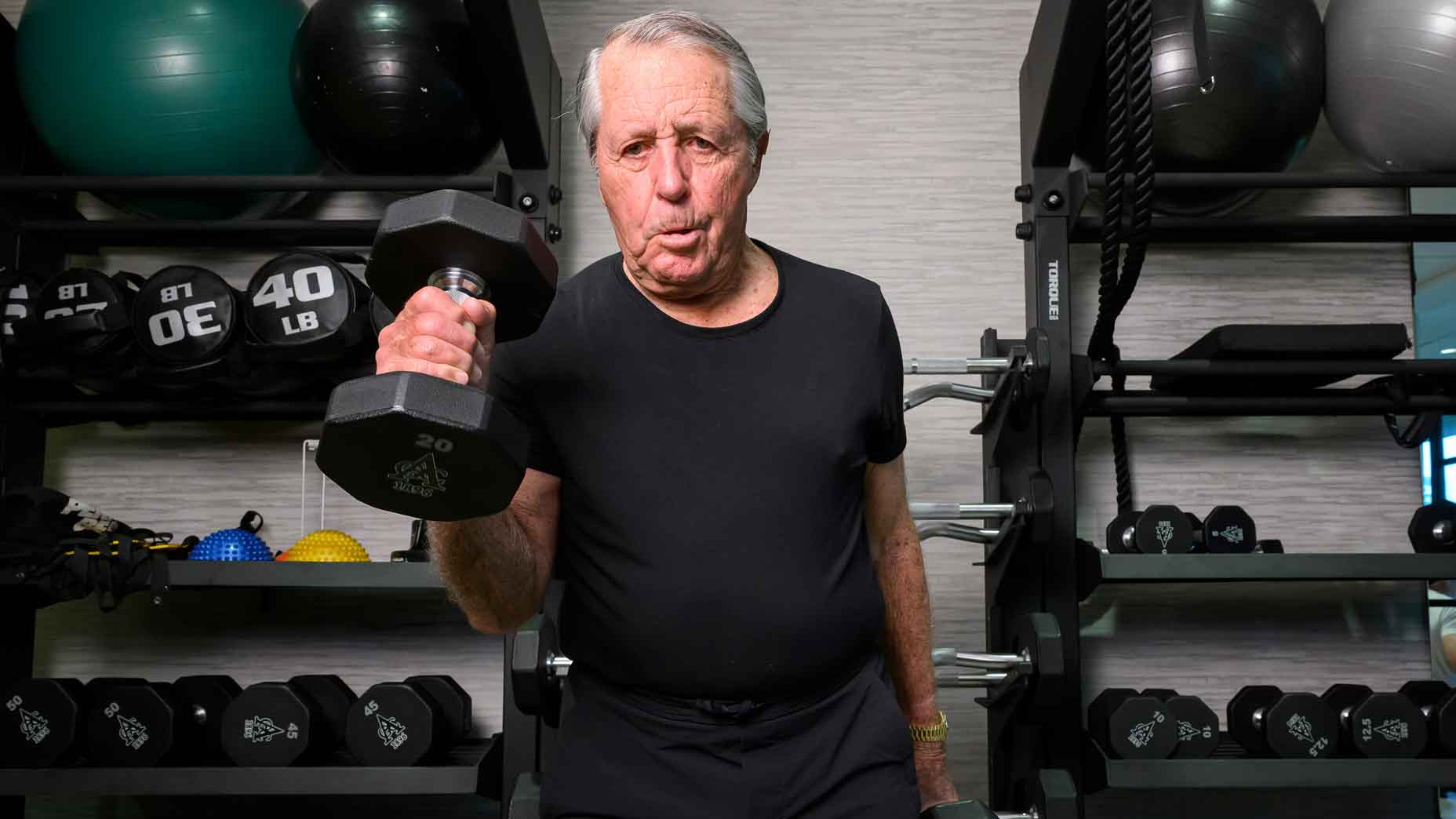

Let those details sink in for a second. A nine-time major champion — who officially turned 90 on Nov. 1 — is headed to the gym where he’ll put 150 pounds on the leg press just to warm up, curl a couple 20-pound dumbbells — “Don’t want more, need to have my touch for when I play later” — before casually closing with a few dead lifts. Then he’s going to play 18 holes where he won a major title in 1962.

“Still shooting under par at my age,” he says confidently, though he’s not boasting, merely stating facts.

Before he bolts to the next part of the day, he thumbs his nose once more at Father Time. He motions over the head trainer in Aronimink’s state-of-the-art gym. Calls him “young man,” because, well, everyone around Gary Player on this misty day in August is young in comparison.

“Put your hand on my head,” Player says firmly. “Don’t move it. I am going to walk away, and I want your hand to stay there. Do not move your hand.”

Player, who stands 5-foot-6, takes a few steps. He turns. He looks at the hand that is 66 inches from the ground. He pauses, because, after all, you’ve got to build the drama. He eyes the trainer once more. Suddenly, Gary Player, aka the Black Knight — who is of course dressed in all black workout attire — goes full Mr. Miyagi. He lets out a yell and unleashes a karate kick, so loose and free and perfect and indescribably impossible. His leg hits the trainer’s hand. Everyone in the room looks at each other, agog.

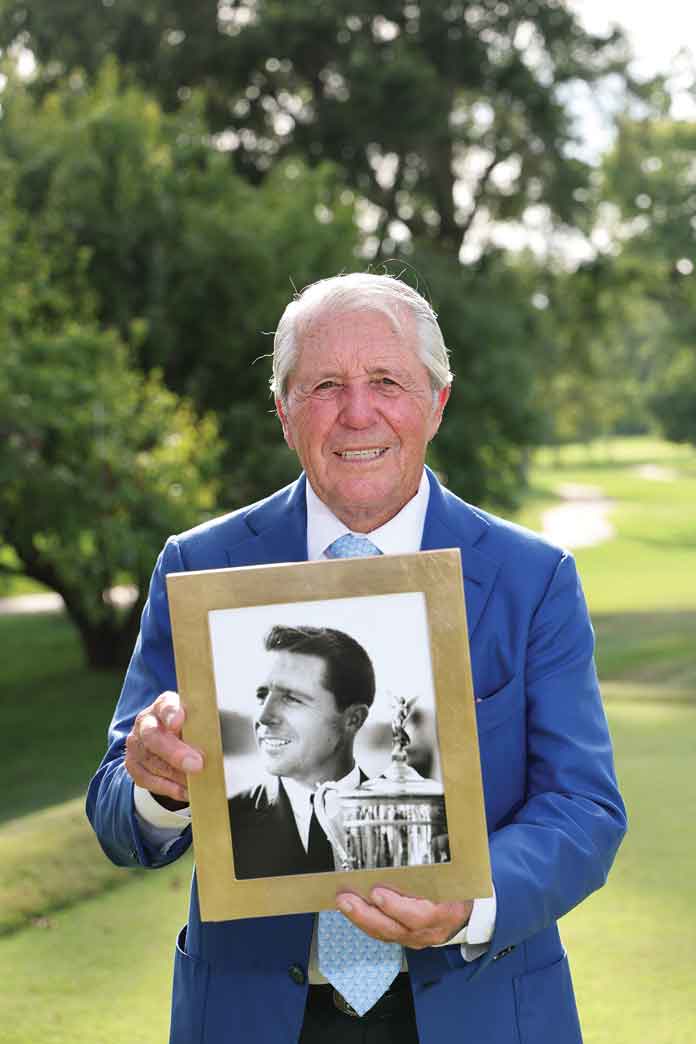

Gary Player holds his portrait from the 1965 U.S. Open at Bellerive.

Jeff Haynes/USGA

Then, just because, Player does it again. Hand on head. Don’t move. Kick. Jaws of onlookers hit floor.

“What happens as you get older?” Player asks, though he already knows the answer. “You fall. I went for my checkup recently. The first thing they asked me was, ‘How many times have you fallen?’ I said, ‘I’ve never fallen.’”

He pauses for a beat. It’s time to build the drama, to underscore the point. He starts pounding on his stomach, hitting himself over and over and over at full strength.

“I won’t fall because my core is sturdy and my legs are strong,” he says as he continues to hammer away at his own midsection.

After all this, the workout, this many trips around the sun, you look for a hitch in his step, a sign that golf’s global ambassador ages just like the rest of us. Perhaps a pause as he navigates a step, a wince as he reaches down to tie his shoes, a sigh as he… Nope. The expression never changes. Instead, he charges forward, on to whatever is next.

“I’m 90,” he says. “I’m still traveling around the world. I’m still working, I don’t believe in retirement. I’m still playing golf four or five times a week.”

Age, the saying goes, is nothing but a number. The hands of time say that on Nov. 1, the great Gary Player turned 90 years old. But in his mind, what is his number, how does he feel, what do his brain and his body tell him?

He doesn’t rush this answer. He wants to really consider it.

“I’d say I feel 60,” he finally says.

As he walks around Aronimink — hey, keep up! — he stops and talks to whomever is in his path. Doesn’t matter who it is — could be a locker room attendant, a member strolling through the clubhouse, a photographer setting up the next image of this ageless legend making long strides without thinking about stopping. The subjects vary — after all, this is a man who has traveled the world, defined a sport alongside Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, sat with Nelson Mandela, teed it up with Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle.

At 90, Player says he still shoots under par.

Edward M. Pio Roda/USGA

The topics vary with each encounter — from fitness to golf to politics to higher education to proper manners. He has opinions on each — strong ones. In each conversation you wait for a moment that suggests he doesn’t remember someone’s name or that he missed something and needs an assist. The body, he has proven, has not slowed. But maybe the mind has grown tired. The delay never comes. He calls each person by name, tells long stories in which he remembers the years, sometimes down to the month and day. Really, who does that? A person in their 40s can’t remember yesterday. A person in their 20s knows what they saw on TikTok about 19 seconds ago. This guy knows every detail.

How long can he keep doing all this? Well, glad you asked.

“My ambition is to reach 100,” he says.

The plan for getting there is the message he is preaching on this day at Aronimink, the same one he has stressed for years and years.

“I cannot do anything more in golf,” Player says. “You’ve had thousands of good golfers. But very few people contribute to health. That’s my dream. The youth of a nation are the trustees of posterity. They are the leaders. A fit nation is a strong nation. That is my dream.

“My itinerary is abnormal. But I’m as strong as hell. Two meals a day. I wouldn’t touch a piece of bacon. I took an oath 27 years ago to never have another ice cream — and I love ice cream — or a piece of bacon. And I haven’t.”

During his competitive playing days, he crisscrossed the globe, winning nine majors and events on six continents. If Antarctica could have hosted a tournament, he would have been on the first tee Thursday morning (or is it night?) and holding a trophy after 72 holes.

“Gary Player might be, pound for pound, the finest player in history,” Nicklaus said a few years ago.

Player has been around so long that his career accomplishments might get lost as the calendar flips, as the decades stack, as the opinions roar. Let’s run through the list, just so we are clear on what Gary Player did on the golf course. Because that cannot be lost in the conversation. He is in the team photo of the best to have ever picked up a club.

He is one of only six players to win the Grand Slam, a club Rory McIlroy joined when he captured the 2025 Masters. He is … wait, it’s just better if he tells you.

“I’ve won the most golf tournaments in the world,” Player says. “I’m the only man to win the Grand Slam on the regular and senior tour. I won more national Opens — U.S., British, Australian — than Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger [Woods] together. And I’ve had more longevity than anyone else in the game. I have traveled more miles than any human being that’s ever lived. I’ve played more golf courses than anybody on the planet. I’ve achieved the ultimate.”

You want to argue with him? Didn’t think so.

Does he have a favorite win, one that stands out across the years and the countless miles? Surely, he won’t answer. After all, this is a man who has 22 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren and famously has an 18-hole qualifier among them to decide who will be his partner at the PNC Championship. For sure he’ll sidestep this one, unable to pick between the majors and the wins across the globe, including in his native South Africa. But immediately, Player has an answer and a story to tell.

“My favorite win was the 1959 British Open,” he says. “To win my first Open at Muirfield, at 23 years of age, the youngest at that stage, it set me up for my life.”

It was a win not even he could see coming. He opened with 75, seven shots off the early pace set by Fred Bullock and Arnold Stickley. He shot 70 in the second round and sat eight shots back. Back then, 36 holes were played on the final day. It would be one of the first times when the characteristics that have defined his 90 years became apparent — endurance and strength.

He posted 70 in the morning to climb into a tie for 10th, four shots behind Bullock and Sam King. He blistered Muirfield in the final round, playing the first 17 holes in 6 under. But he made double bogey at the last, a mistake he was sure would cost him the title. Even with the miscue, though, the 68 was the lowest score of the final round, good for a two-stroke victory.

“Grit is what Gary Player is all about,” Tom Watson once said. “Grit. That’s how I define Gary Player. There’s never a shot that he ever plays loosely. That’s what makes a true champion.”

While the Open at Muirfield stands out, there were other memorable victories along the way. He outlasted Arnold Palmer to win his first Masters in 1961, and 17 years later won his third and final green jacket by shooting a final-round 64 to erase a seven-shot deficit and

defeat Hubert Green. In 1962, when he won at Aronimink, he held off a weekend charge from Nicklaus. This year, he celebrated the 60th anniversary of his lone U.S. Open title, in 1965 at Bellerive Country Club in St. Louis, in an 18-hole playoff over Kel Nagle that completed the career Grand Slam.

It’s that triumph that cemented his place among the all-time greats and forever locked him into the “Big Three” with Palmer and Nicklaus.

“The best of friends from the start to the finish,” Player says of their relationship. “For some unknown reason, it jived from the beginning to the end. What wonderful men. What they did for America, as ambassadors, is unbelievable.”

The three names have always flowed so perfectly – Palmer, Nicklaus, Player. As he reminisces about his old friends, what they mean to him, what they mean to the sport, the conversation shifts just to Player. Like them, he has done so much. Like them, his memory will live on when he is done.

So, he is asked, what do you want your legacy to be?

“If there is a legacy, I want it to be a man who helped changed the lives of millions of people,” Player says. “Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and I must have raised over $600 million for charities in our lives. I have charities that I am running — the Gary and Vivienne Player Foundation — I’ve built schools in South Africa, hospitals, churches. You know why? I suffered as a kid. Really suffered. Mother dying. Father working 8,000 feet down in a gold mine. My brother left high school in South Africa and went to war for the American flag at 17. I have so much admiration and gratitude for America, that I want people to say one day that this guy, he loved people.”

He has done very little of this quietly, stating opinions — some popular, some less so — along the way. He has tussled with Augusta National. He’s weighed in on the swings and the games of modern players. Ask him a question, he will give you an answer — sometimes whether you like it or not. So be careful when you ask if the sport of golf is broken, if it needs fixing.

“Yes, it does need fixing,” Player says.

He needs to be up the stairs at Aronimink for his photo shoot. He has picked out his wardrobe. Not a hair out of place. His afternoon tee time is approaching, so an already fast pace to the day has picked up. But the state of golf – this requires his full attention. In his mind, it requires everyone’s attention. He stops. Everything else can wait.

“You have to cut the ball back,” he says, his voice getting louder. “Golf is a different game for a club member than it is for a PGA Tour player. For a Tour player, I’d cut the ball back 60 yards. If we don’t, in 30 years’ time, they are going to be hitting the ball 450 yards — maybe farther. The concept of golf is gone; par 3, par 4, par 5… all gone. There is no such thing as a par 5 in the world today. It’s just gone. Every time they play golf now, it’s a par 68. The ball goes so much farther. And the metal heads. I’m 90 years old and I might miss one fairway with these clubs. The clubs themselves, the mowers and the conditions of the fairways, the bunkers are raked with machines. We have to do something.”

As he starts walking again, he allows his mind to wander a bit. What else might he have accomplished if the world was like this during his youth? The technology? The conditioning of these architectural masterpieces? The private planes that make getting around the globe so much easier?

“Traveling back and forth, back and forth,” he says, shaking his head, unable to fathom a guess at how many miles he has traveled. “When I first traveled 60 years ago, there were no jets. We traveled from South Africa to America, for example, it took us over 40 hours — four stops. I’ve lived in an airplane for 74 years.”

But his strongest opinions are regarding the health of a nation. Whatever time he has left — and he feels like he still has plenty — will be spent talking about physical fitness. He shakes his head at the choices being made — by parents, by children, by those playing the sport he loves.

“First message is, if you want to live a long time and be fit, two meals a day,” he says. “Cut out bread. As a pro golfer, you’ve got food in the locker room, you’ve got food at the first tee, food at the 10th tee, food at the 18th. There’s food everywhere, and people just eat, eat, eat. Obesity is what’s killing more people than anything.

“This is the greatest country in the world. How do you get them to be healthy? How do you get them to be interested in their bodies? It is easier for a camel to get through the eye of a needle than to get people healthy. People are so obese. They don’t understand if you are 5 pounds overweight, 10 pounds overweight, it is serious. Throw away the damn phone.”

He says this over and over on this day. He vows to say it over and over until people listen or until he can say it no more.

For Player, physical fitness is always top of mind.

Edward M. Pio Roda/USGA

As he nears the stairs, he stops to look at the glass case, at the young version of himself from 63 years earlier. In one photo he is peeking inside the lid of the PGA Championship trophy he won here. In another, he sees a young man in a tuxedo, his eyes as alive in that photo as they are in this moment.

“Why me? Millions of people have tried, millions are trying, and I’ve done it,” he says. “Gratitude. The older I get, the more my life is filled with love and gratitude.”

He goes up the stairs, tells stories as the camera clicks and the lights flash. He talks about his father and about the first time he picked up a club.

“I was 14 years old, and I went with my dad,” Player says. “He wanted me to play golf. I said, ‘Dad, I’m playing rugby and soccer and cricket and swimming.’ He said, ‘Just come with me.’ Thank God I did. Imagine if I never went?”

He says if he had not been a champion golfer, he would have been a schoolteacher. Outside, the mist has turned to a consistent drizzle, but that doesn’t stop him. He’s got golf to play. He walks down the hallway, toward the stairs. He starts reciting statistics about how many people fall down the stairs each year.

As he walks, he is asked for a swing thought. It seems wrong to spend so much time with someone who has done so much in the sport without asking for a tip.

“For golf, the most important things are your legs and your core,” Player says, and now, again, in the middle of the staircase, he is hitting himself in the stomach to illustrate the point. “Not your arms. You don’t hit the ball with your arms. You hit the ball with your core.”

Perhaps, given the statistics he recited 30 seconds earlier, the lesson could be conducted at the bottom of the stairs? The goal is to make sure he gets to 90, to the big party in Sun City, South Africa; to a ceremony at Bellerive; to the first tee at Augusta National in April. To the next workout.

Instead, still standing on the staircase, he starts explaining proper posture and the finer points of the takeaway. He won’t move, because, just as he told his doctor a few days earlier, Gary Player doesn’t fall. He smiles. He says one more time just how grateful he is. He turns and confidently walks down the hall to all that’s ahead.