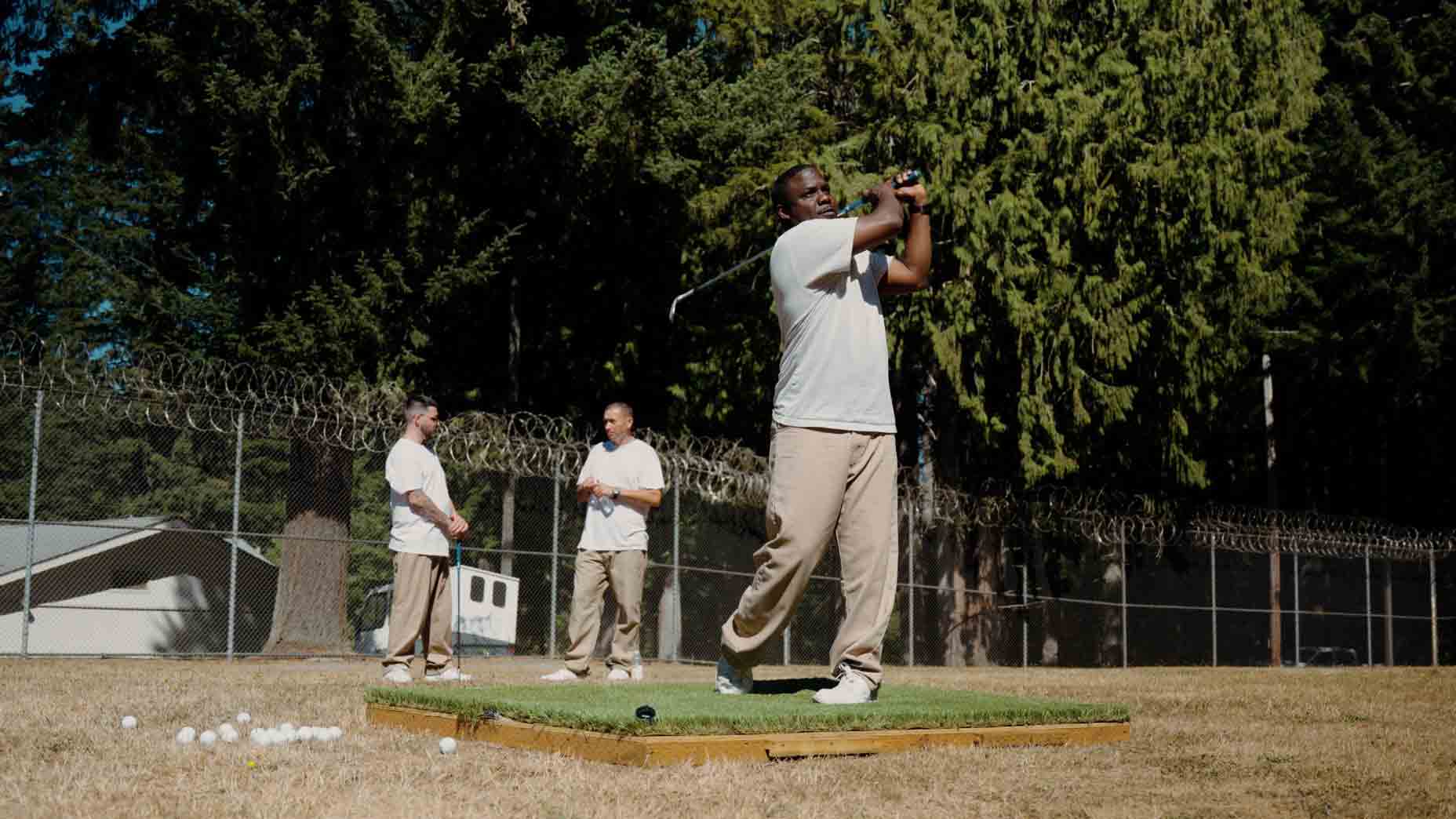

LITTLEROCK, Wash. — Nico flings back a 3-foot dreadlock. He’s up now.

Ahead of him on the tee, Rodron went left, and G went right, so he certainly would be forgiven if his ball also roamed, though straight is the idea. Instead, his ball innocently squirts a couple of inches backward when his driver slides under it. All tee. Nico points at a bystander capturing the scene with his phone and mutters to him to cut that part.

He reloads. And re-misses.

Nico misses for a third time and laughs. Those around him howl. “If he does it a fourth time, I’m quitting,” Rodron cracks.

Some swings here. Some potshots there. That’s golf, in its most unpretentious form. It’s a chance to play, an opportunity to commune and a way to let go, no matter who you are or how you arrived.

Even if where you are is in prison.

“>

Nico and Rodron are both inmates at Cedar Creek Corrections Center, a minimum-security prison outside Olympia, Wash., that houses approximately 450 prisoners who have less than six years left on their sentences. Some of the offenses are severe. Some of the time locked up spans a generation.

And some of the inmates are part of a radical social experiment: that golf can serve as rehabilitation for those whom society would rather forget.

But they would prefer for you to call it Cedar Creek Golf Club.

The prison superintendent is Tim Thrasher, a tattooed, goateed, Harley Davidson-driving former Army brat. But he is also a golfer, a golf romantic, really, the type who believes in the game’s rules and etiquette and that sort of thing, which led him to think that there would be no better activity for Cedar Creek. After all, the goal is for tenants to leave its walls equipped to be your next-door neighbors again.

Then again, Thrasher is placing woods and irons in the hands of inmates. Weapons. Isn’t that naive? Foolhardy?

And isn’t prison designed to punish?

That’s what this country wants, one expert says. A “tough on crime” stance means no games, and certainly not golf, stereotyped to be the pastime of the elite.

But that’s not effective, says Professor Kimora, an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York who has studied and worked at prisons throughout the world.

“Those guys are a small minority of people that are actually probably going to do extremely well when they get out,” she said. “Not just survive, they’re going to thrive because of what they’re doing. That’s how valuable what’s going on here is.

“And it’s so rare.”

Thrasher started CCGC about three years ago. And about a year and a half ago, Nico got curious. His old neighborhood has a golf course, though he said he had questions. Do you just pull up and play? What does it cost? Where do you start? So he would only drive past.

“Speaking from my own personal experiences, this is new,” Nico said. “I’m 30 years old and this is completely new. And it’s always something you see as prestige for me. So it’s like, OK, I’m in this situation and it does give me a form of therapy to come up here and be like, OK, I’m about to go golf.

“I never thought I’d be golfing, let alone in prison.”

Now if only Nico could hit that driver. He tried a fourth time.

After he shoved away his hair again, his inked forearms muscled the club toward the ball — and it took flight. His fellow golfers, all dressed in the prison’s garb of white T-shirts and tan pants, cheered. So did Thrasher. He was leaning up against a 15-foot fence rimmed with barbed wire a few feet away.

Tejuan of the Cedar Creek Golf Club.

Darren Riehl

TEJUAN’S BALL WENT OVER THE FENCE. Everyone calls him Zeus, and of course a dude called Zeus can clear that fence. His swing is whippy but governed. Besides playing golf, he lifts, and he prays. Inmates remind him of his shorter height, but he plays along — he also asks Thrasher when the kiddie clubs are coming.

But what you see first is the ink. It’s all over Tejuan. On his shaved head. His face. His arms. He has operated tattoo parlors all over the country.

He says the silent part out loud: “I definitely don’t look like your average golfer.”

Then again, who does here?

The routine is dull at Cedar Creek. Inmates rise around 5:30 a.m., from either a one- or two-bedroom unit without bars. They go to work on construction, maintenance and outdoors jobs, among others. Classes are available. Therapy, too. Drugs are a constant worry. Downtime is spent in various ways, though pickleball is king.

And golf is played.

By Tejuan.

He still seems awed by the idea.

“Never in a million years,” he said. “Never. Never.”

Why?

He had heard prison stories. He knew the prison stereotypes. He expected four-letter words, just not “g-o-l-f.” He thought he might play football, like in “The Longest Yard.” Never golf.

“It’s never something that could actually advance you in life, like golf could actually advance you in life,” Tejuan said. “Just the principles that you apply when you play golf. Then when you apply that to your life, you know, and also just the socialization that you actually get when you go to golf courses.

“There’s a different element at golf courses. There’s a different lifestyle that comes with playing golf. It’s an expensive sport, so you have to actually have a job. You have to pay for everything. So it keeps you working. It’s not like anything else, and it also, I’ll say, gives you a leg up.”

To be clear, there is golf inside Cedar Creek, but there is no golf course. The participants gather on a softball field during the summer and in a gym the rest of the year. Play is from 6:30 to 8:30 every Wednesday night; a confirmation is sent over email, and a few minutes before things start, an announcement crackles the yard speakers: “Last call for golfers.” They hit pitch shots first, with foam balls, to a carpeted green guarded by a small bunker on its back-right side. Then 75-yard shots, atop a wooden pallet fitted with a green mat. Finally, they hit drives toward the left-field fence and towering Washington pines. (Balls that carry the obstacle are eventually picked up by prison guards — and dropped outside of Thrasher’s office.) Everything is a competition, and experience varies. The winners earn toiletries, a prized possession in prison. Smack is given to all. Even to Thrasher, who also plays.

To Tejuan, golf is new. His grandfather once tried to teach him, but that was short-lived after Tejuan mostly kicked the golf balls. Recently, he reconnected with his son after a seven-year separation, and they talked golf. His son watched a local news report on Cedar Creek’s program, and there was his dad, playing golf, on TV. He felt proud. Dad, too. No matter that he was playing golf inside a prison.

No matter his appearance.

Golf, he said, has given him the chance “to be around people that I probably wouldn’t.” The reverse could be true there, too — those people probably wouldn’t have been around him, either. That’s changed him. He had once built up hostility. But with golf and its interactions, that feels lessened now. That’s freeing.

“The only way I can say it is I guess it helps with my self-image, my personal thoughts on how I’m actually perceived by the world around me,” Tejuan said.

“Like I say, I forget I look like this. I’ve been in certain situations where people don’t want to talk to me. … First impression is everything. So, like, if you never get a chance to talk to me or interact with me and you look at me, I look like something in a zoo. You know, I get that.”

Members of the Cedar Creek Golf Club.

Darren Riehl

SHOULD INMATES BE ALLOWED TO PLAY GOLF? Thrasher has heard that one regularly. But maybe that question can be answered with another question:

Should former inmates be allowed to play golf with their prison superintendent?

Brandon has. He played in CCGC while incarcerated, and on a recent Sunday afternoon, he played nine holes on a real course with Thrasher. He was nervous; it was his first actual round in years, and, as he put it, “when you’re part of the criminal underworld, you don’t exactly have time for golf.” Brandon dressed like a Tour pro — red Titleist hat, a white polo shirt, blue pants — though Thrasher wondered if the patriotic-looking ensemble was a nod to the late Hulk Hogan.

Thrasher, who’s a single-digit handicap, also told Brandon on the sixth tee that if he could beat him on just one hole on the way in, he would give him one of the T-shirts he recently had made for CCGC. Thrasher’s first shot found water; Brandon laid up. Game on. But Brandon’s second shot also found water after he topped it. Then he chunked one. Thrasher grabbed his phone and hit the play button. David Bowie and Freddie Mercury began to sing.

Pressure

Pushing down on me

Pressing down on you

No man ask for

Under pressure

Yeah, yeah, Brandon said.

Every inmate, present or past, wants to beat Thrasher, and he loves it more than he loves making birdies. He has been around the game his whole life. Mom worked at a course. Dad taught him how to play. His dad also once worked with the father of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain. But if you’re talking ’90’s Seattle music, Thrasher is an Alice in Chains guy. And a Vegas guy; last month, he went to see a fight. But golf is his thing, and when he was hired as Cedar Creek’s superintendent in 2022, he wondered about bringing the game with him. He watched the inmates. He talked with the staff. Thrasher hung flyers, about 75 inmates responded, and 15 were chosen. Opening day came in October 2022.

“A hot mess,” Thrasher said.

They made tweaks — the wisest among them: using foam balls for indoor play — but most of the equipment remains his, and the time he invests in the program is also his own. CCGC also has pick ’em pools for all of the majors, and, over popcorn and Gatorade, they watch Netflix’s “Full Swing,” then review it. Naturally, they are enthralled by the story of pro Ryan Peake, who spent five years in prison before winning an Asian Tour event earlier this year and qualifying for the Open Championship.

For the inmates, one of the most surreal parts of CCGC is that they’re doing all of this with the super, of all people.

The man holding the key.

The enemy.

There’s an appeal here, though. Not only can you beat him, but you also don’t have to worry about him beating you down.

Rodron called Thrasher genuine.

Nico said he was present.

Brandon said their round felt almost as if he were playing with a friend.

“My old cellie was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to go to Cedar Creek; they have golf and all this other stuff,’” Brandon said. “But I don’t want to say prison was fun — it’s something I don’t want to do again — but it made it livable because you can’t be locked up 24 hours a day. They’re going to come out and just not be normal people in society, so I think they made it, as much as possible, as normal as they could.

“I’m not saying I had a great time there, but compared to what people are doing on the streets now with the fentanyl and everything else, I take it as a blessing that I had a reset in life, that I’m not just a statistic.”

Should inmates be allowed to play golf?

To Thrasher, golf is just the medium.

If the inmates can play golf with him — the prison superintendent, their antagonist — think of how they will interact with everyone else.

“It’s going to be second nature to them that they’re going to be nice to people, that they’re going to not break rules anymore,” Professor Kimora said. “The fact that they were invited to do this stuff means that those folks trusted them. There’s no relationship if there’s no trust.

“What kinds of relationships do people have in prison? They’re suspicious of everybody, right?”

Rodron of Cedar Creek Golf Club.

Darren Riehl

BUT SHOULD INMATES GET TO LEAVE THE PRISON WALLS TO PLAY GOLF ON AN ACTUAL COURSE? When Rodron heard that was a possibility, he was in. And when he reached the course on a Tuesday afternoon in July, you could hear Rodron. On the tee box. In the fairway. On the green. He’s a talker. Here’s how he described four CCGC members — along with Thrasher and one of the prison’s officers:

“Mike, he’s too quiet. He’s trash.”

“Tejuan, tattooed. When I first met him, I was scared of him. But that’s my guy.”

“Devin, we butt heads all the time. He’s a piece of crap, too.”

“G’s the guy. He’s the leader.”

And Thrasher? Rodron has golf thoughts.

“I can’t wait to get out and kick his butt. Can’t wait. Him and Doug. Doug’s my boss at maintenance. The biggest shit-talker in the world. Can I say that? The biggest trash-talker.”

Thrasher calls Rodron, a Mississippi native, “the Mouth of the South.” But he can back up the smack. Rodron is CCGC’s best player. He says he has played on courses you’ve heard of, and with a few golfers you know. He says his father was an Alabama judge, and his uncle, a probation officer, taught him golf. Rodron then showed his daughter and son how to play. They’re everything to him. And they should have seen their dad at The Home Course, about 20 minutes from Olympia. At CCGC’s first real outing, on a course that has hosted USGA events, Rodron hit the first shot and found the first fairway.

Thrasher had coordinated the day through the course, the Pacific Northwest Golf Association and the prison, after thinking of ways to further develop the program. Five inmates attended, each paired with an officer, and they played a four-hole scramble; they also listened to a job presentation by the course’s maintenance staff.

On the van ride over, Thrasher handed out the T-shirts he had made — red with a logo over the heart displaying “CCGC,” a skull and two crossbones in the shape of golf clubs. As a state patrol car drove past, someone shouted to watch the speed limit, to which Rodron responded: “What are they going to do, arrest us?” At another point, Thrasher deadpanned: “What if this were fake news and we were taking you all to max security?”

Then they played golf. Shots were hit. Shots were mishit. Potshots were fired. On the par-5 third hole, Thrasher dropped an iron to 3 feet. All seven players missed the putt. That was a lowlight, for golf purposes, but a highlight for the trash talk. On the last hole, a par-3, everyone teed off together.

In six years or less, everyone now at Cedar Creek will be able to play The Home Course or anywhere else seven days a week, should they choose. Rodron says he’ll be back. On Day 1 on the outside, he’ll play with his kids. But prisons such as Cedar Creek stare at a grim statistic: According to the U.S. Department of Justice, about two-thirds of released inmates will eventually be reincarcerated, or about 425,000 individuals a year. CCGC’s number? So far, it’s zero, but the program is in its nascent stages.

Still, it’s encouraging, and CCGC’s best golfer has an idea of why the program may be working.

“When you get sentenced by the judge, that’s it,” Rodron said. “You go, you do time. But if you want me to come back into society a better person, then give me all the tools to do that. So what Thrasher is doing is a great thing. A lot of people in the community might not see it that way. But it’s bettering these men. You can see it. The camaraderie, the diversity.

“Most of us wouldn’t even talk to each other in prison, because of prison politics, they call it. But in golf, we do.”

Something deeper may also be at work. Social psychologists who have worked in prisons will tell you that what inmates need most is a sense of humanity. Rodron says that at one point at The Home Course, he shut his eyes and thought the excursion was a real round.

What is the byproduct of that?

Hopefully, inmates feel rehabilitated.

And what’s the derivative of that?

They don’t return.

“It’s about humans interacting with other humans,” Professor Kimora said. “If people could get away from this attitude that those people who are incarcerated are meaningless … that could change the whole correctional system in this country.”

Late on that Tuesday afternoon, Cedar Creek’s van pulled away from The Home Course. Back to prison.

On Wednesdays, they will play at CCGC again. Tejuan will smack one, and Rodron will talk his smack. Maybe Nico will connect with the driver. Whether the program will actually work, though, is anyone’s guess, no matter its intent.

But a tee time has already been made.

On the ride to The Home Course, Thrasher had asked the five golfers when they were being released. Soon, some said. A couple of years, another chimed in. Good enough, Thrasher said.

There would have to be a reunion.

“We’re all playing together in 2027 then.”

Five ex-prisoners and a prison superintendent. Six golfers.

Maybe one or two drivers under the tee.

The author can be reached at nick.piastowski@golf.com.