An iPad delivered the cold, hard truth: The United States was going to lose the 2012 Ryder Cup.

American captain Davis Love III stood dead in his tracks on one of Medinah Country Club’s signature bridges. Dru Love, his son, anxiously held the device, displaying the stats and the scores from Sunday’s singles matches against Team Europe.

“What in the world is happening?” Love asked, peering over his son’s shoulder.

The two stared down at the screen. Then they stared at each other. The scenarios started to unfold before their eyes in a matter of minutes. One improbable point-clinching shot after the next, and the American team’s nightmare was suddenly playing out in real life. The dominoes — they would not stop falling.

“We looked at it and we went, ‘Oh, crap. We could actually lose this.’ That’s the momentum shift,” Love says, 13 years after the Europeans staged the largest Ryder Cup comeback in 85 years, which was quickly coined the “Miracle at Medinah.”

“Little things happened that flipped the momentum all at the wrong time. It might have been an hour, it might have been 30 minutes. Boom, boom, boom — we’re in trouble.”

The Ryder Cup “golden hour” will be feared by one team and welcomed by the other, but every time the biennial competition rolls around, the phenomenon is bound to appear. In the modern era of an event that produces predictable results because of a strong home-course advantage, the recurring trend is hidden in plain sight.

At Bethpage Black, host of this week’s 2025 cup, the American and the European teams each come armed with rosters of the best golfers on the planet. The cup will be competitive. However, there is always a possibility that one team pulls dramatically ahead.

That’s why the beauty of the Ryder Cup rests in this Sunday ritual — that fleeting window when the best-case outcomes start to align, the energy pulses between pairings and the unlikely suddenly feels possible.

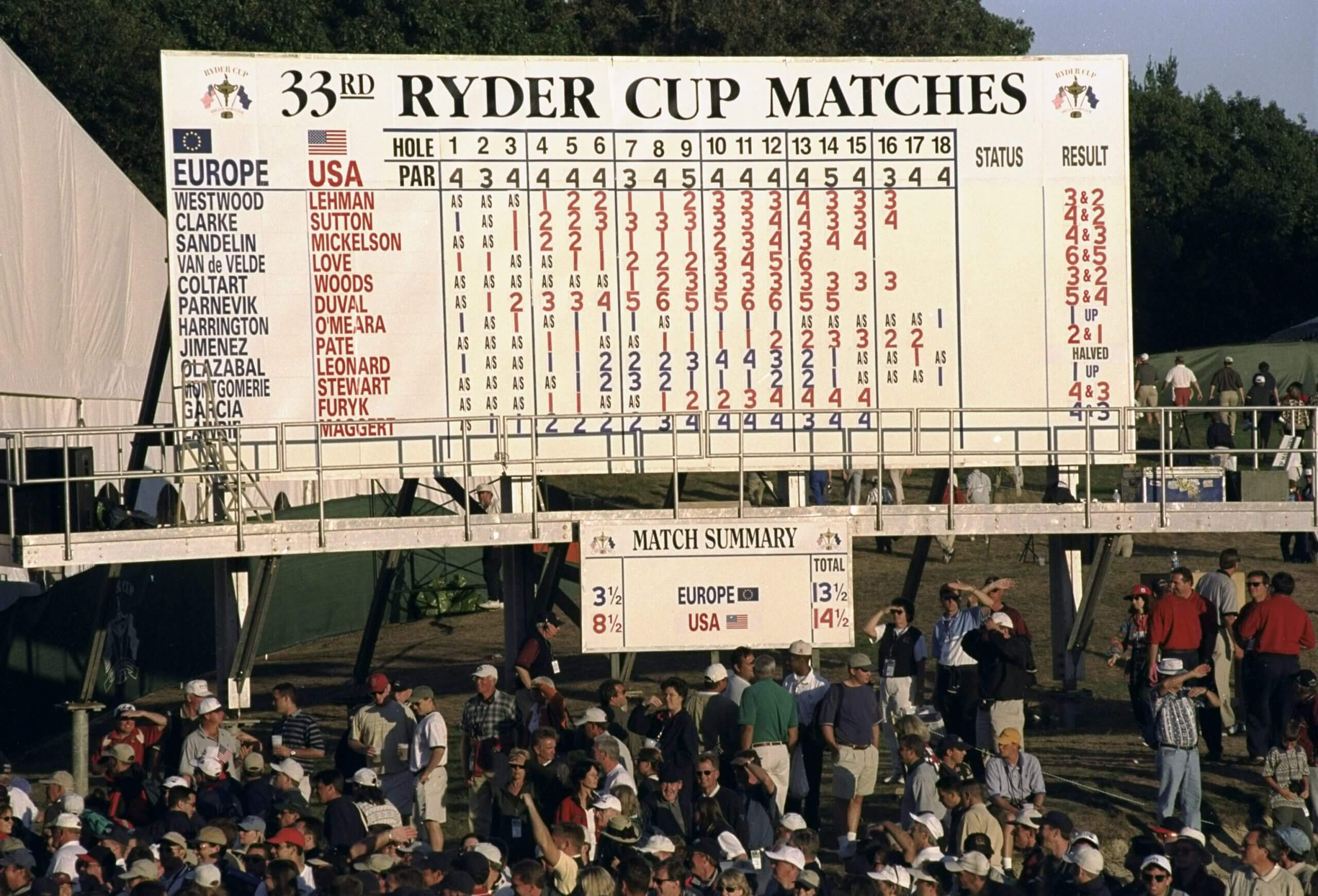

The scoreboard on Sunday at the 1999 Ryder Cup told the story of the American comeback. (Harry How / Allsport via Getty Images)

Whether there’s a sliver of hope or a turning of the tides, this hour will come. Sunday singles sessions at the Ryder Cup have not typically altered the outcome of the competition. However, at some point during the day, no matter where each team stands when it begins, things will start to revert to that magnetic middle.

The impending blowout will suddenly feel like a neck-and-neck race. And that magic hour will be felt all around the property, because history knows all too well that the flip is indeed possible.

Just look at Medinah. Or Brookline.

“No matter what the deficit is, up, down, close, big margin, there is always that time period. It seems like when all 12 matches have started, and the first match is on the back nine, and you think, OK, wow, this could actually flip today,” says Joe LaCava, who caddied for Tiger Woods in his last Ryder Cup player appearance and now carries the bag of U.S. team member Patrick Cantlay. “It’s amazing how fast it can flip, feel like it’s going to flip, and then flip the other way.”

Over the past 10 Ryder Cups, the average margin in points heading into Sunday singles has been 3.7, and the average eventual winner’s margin is even larger — 5.8 points. Yet, aside from a select few, namely the American domination in 2021 at Whistling Straits, those final days have always seemed to provide moments of juncture. They emerge for a reason. The golden hour stems from the very nature and ethos of the Ryder Cup’s competitive makeup.

The lead-up to that inevitable window begins long before the first shots are struck on Sunday morning. When the head-to-head matches are set on Saturday evening, an internal calculation begins. Who needs a win early to give their team a jolt? Who could manufacture a potential upset and throw things for a loop? The players and caddies will have it mapped out, whether spoken or not, to prepare themselves for how the day might unfold.

“If you play No. 9, 10, 11 or 12, you’re on the range and you’re watching the early coverage. You’re living and dying with what’s going on out there ahead of you. There’s no question that the guys that go out early can give you momentum,” says Jim “Bones” Mackay, who caddied in 12 Ryder Cups for Phil Mickelson and Justin Thomas, and has attended every cup since 1993.

In 1999, during the “Battle of Brookline,” the Americans miraculously came back from a four-point deficit heading into the final day of the event by winning the first six matches of Sunday singles. No team had ever surged from more than two points down at the start of the last session of the event.

Ben Crenshaw, the U.S. captain, front-loaded his lineup, while European Mark James decided to do the opposite. Sent out third, fourth and fifth, respectively, Mickelson, Love and Woods did precisely what they were there to do, and snatched the momentum.

“On Sundays, if you see all the points up on the board and everybody’s 1 up or 1 down,” Love says. “It’s like, wow, if all five of those in the middle slipped, we’re done.”

Even the sight of a potential wave can propel the trend. Leaderboard watchers thrive. And those who shy away from knowing where they stand in tournaments have to be prepared to operate otherwise. Because at the Ryder Cup, even if you aren’t keeping tabs on the standings of the event, the crowd will let you know.

You cannot escape the auditory cues of the shift, even if they are happening on parts of the golf course that typically wouldn’t concern you in an individual event. The required psychological approach to a Ryder Cup is unlike anything a player will experience in his career.

“If a guy says he’s not looking at the leaderboard at a Ryder Cup, he’s flat out lying,” LaCava says.

Thirteen years after Brookline, there was Medinah, with European captain and legend José María Olazábal leading the charge. (Andy Lyons / Getty Images)

On the surface, the Americans won the 2008 Ryder Cup at Valhalla dominantly, 16 1/2 to 11 ½ — the largest winning margin for the U.S. since 1981. However, a blue wave transpired early on Sunday in Kentucky in response to rookie Anthony Kim’s 5 and 4 victory over Sergio Garcia. Europe won the next two matches — Justin Rose upset Mickelson, and Robert Karlsson defeated Justin Leonard.

And then, moments after sinking a birdie putt on the 17th hole to go 1 up over Paul Casey, Mahan hit his drive in the water on the 18th, losing the hole and halving the match. The Americans only had a two-point lead headed into that final day. It could have started right there. It didn’t, though.

“I just remember looking up about halfway through and going, oh boy, I see a path,” Wood says.

Just two years ago in Rome, the Europeans endured that last-second scare. The first six matches on the board were European dominant, and the home team only needed a half-point to secure its victory. However, the leaderboard was telling a new story: Max Homa 1 up on 17, Brooks Koepka 3 up through 15, Thomas 2 up on 14, Xander Schauffele 2 up through 13 and Jordan Spieth 1 up on 12.

A mighty block of red served the Americans a shot glass full of hope. For the next hour, the team held the door open with everything they had left. However, it was too late, and it would never be enough.

Sunday singles matches count for 43 percent of the available points in the Ryder Cup. When each player is suddenly back on their own, playing as a one-man show, doing what they can to will the team and themselves on, the pressure of the Ryder Cup mounts in a new way. That’s why the golden hour always comes — that’s why momentum in the Ryder Cup is a real, tangible thing. As the minutes tick by, the inner realizations swirl for the losing team: This is our last shot.

“Sunday is a reckoning for the losing team to throw the kitchen sink at things, come off the ropes and start swinging punches,” says Paul McGinley, former European Ryder Cup captain and player.

And if those last-ditch efforts start to work, the losing team’s movements can, in turn, trigger the winning team’s final push.

McGinley recites his favorite Woods quote: “The best way to defend a lead is to extend it.”

This is when the golden hour begins to draw its curtains. The possibilities become figments of the imagination. And the two-year-long wait to the next Ryder Cup begins anew.

(Top photo of Luke Donald: Richard Heathcote / Getty Images)