Mark Wagner

Special to ICT

Land is deeply embedded in Native cultures, and the game of golf, in many ways, is also about land.

A golf course requires the most land of any of our sports, land that is the combined efforts of Mother Nature and the artistry of human hands. The only uniform aspect of the sport is the size of the cup, a 4.5-inch opening in the earth that is the site of the joys and sorrows — frustrations and aspirations — of the some-odd 46 million golfers in the country.

While the sport is often associated with White elitism and criticized as a “rich man’s game,” Native people have embraced the sport since Oscar Smith Bunn, Shinnecock/Montauk, a gifted golf instructor and club-maker, played in the U.S. Open golf tournaments in 1896 and 1899.

Native players have made their mark ever since, from Althea Gibson, Lumbee, to Rod Curl, Wintu; from Orville Moody, Choctaw, to Notah Begay lll, Pueblo/Navajo; and a new generation including Gene Webster Jr., Navajo and Ojibwe; Aidan Thomas, Laguna Pueblo; Maddison Long, Navajo and Coeur d’Alene; and Payton Beans Factor, Chickasaw.

This long history of Native golf took a turn in the 1970s and 1980s, when tribes, aided by the revenues from gaming and fee-to-trust programs, began to develop their own golf courses on tribal lands.

The Mescalero Apaches started things off with the Inn of the Mountain Gods in 1975. Today, the celebration of land and design, recreation and economy on Native land continues to grow, as more than 60 tribes, bands and nations have gotten into the game, stretching across the United States from Hawai’i and California to the East Coast.

As of this writing, no one alive has played all the Native-owned courses. But let’s imagine for a moment a world in which a tourism company announces a package where efforts and resources go toward honoring the elders and cultures of our tribes.

Impossible? It’s just a matter of time.

A history of stewardship

The Inn of the Mountain Gods was followed by Cochiti Golf Club in 1981 in Cochiti Lake, New Mexico, on lands of the Cochiti Pueblo.

The golf courses that followed have combined the economic visions of the tribes with renowned course designers and players.

One of the most economically successful tribes in America — the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community of Minnesota — added golf to their holdings in 2002 when they purchased Lone Pine Country Club.. The course was remodeled by architects Garrett Gill and Paul Miller and reopened in late summer 2005 as The Meadows at Mystic Lake. The facility has since drawn numerous awards and recognitions.

In Minnesota, where golf is, at most, a five-month season, the arrangement points toward what is to come. Golf has woven its way into Native culture, and the result has been a new generation of golfers, teachers, and golf industry workers among our First People.

Among this new generation is Michael Powell, Osage Nation, a Professional Golf Association golf professional at Firekeeper Golf Course in Mayetta, Kansas, owned and operated by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

“The course sneaks up on you, how good it is,” Powell told ICT. “I mean, let’s face it, reservations were not selected for deeds of access and prime real estate. But we’ve made something great. And we are fortunate that we are within a short drive of major metro areas, pulling from several populations there.”

The Firekeeper golf course, designed by Jeffrey Brauer and Navajo golfer Notah Begay lll, is owned by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Credit: Courtesy photo

The Firekeeper golf course, designed by Jeffrey Brauer and Navajo golfer Notah Begay lll, is owned by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. Credit: Courtesy photo

Firekeeper, designed by Jeffrey Brauer and Notah Begay lll, sits on land near the end of the Trail of Tears, a fact not lost on Powell.

“A lot of tribes got shoved off into the middle of nowhere,” he said. “Well, nowhere is now this beautiful golf course. . .. When I hand it off, I want to say that I have been a good steward. The land is going to outlive us.”

This focus on stewardship of land was also on display when Sewailo Golf Club opened in 2012, a project of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe in Tucson, Arizona.

“You cannot just come in, fire up a bunch of bulldozers and start changing the landscape,” Peter Yucupicio, then-chairman of the Pascua Yaqui, said at the opening. “You have to be able to first talk to the land and ask for permission. We ask our Creator and the ground, the trees, the rocks. . . We say, we’re going to change you a little bit, but all the things we’re doing here are for everyone’s benefit — the tribe, all of Tucson, all of Southern Arizona.”

Sewailo is another design by Begay, and he was also on hand for the opening, which included a deer dancer who came out of nearby desert shrubbery to bless the grounds. The course is a celebrated “destination links” course that is also the home of the University of Arizona men’s and women’s golf teams.

At its opening, Begay noted, “These projects start from the standpoint of culture, and it’s important we maintain and respect the culture and traditions of the communities we work with. As with all projects I work on, based on the teachings of my mother and grandmother, I ask for guidance from our Creator as we shape these holes.”

Jay Garcia Hatra’muhnee, chair of the Santa Ana Golf Corporation of the Santa Ana Pueblo in New Mexico, echoes the same themes. The Pueblo operates two courses: The Santa Ana Golf Club and the acclaimed Twin Warriors Golf Club.

“In every generation, respect for land has always existed and with this has opened the opportunity for recreational and wellness development by tribes such as golf facilities, soccer fields, baseball and softball fields, basketball gymnasiums, Wellness facilities, skate parks and running/walking trails, equestrian facilities,” he said.

Garcia, along with Tribal Board Director Larry Pasqual, began the Native American Open golf tournament in 2020, featuring Native golfers from across the country and Canada.

“We celebrate Native culture every day,” Garcia said. “Santa Ana Golf Club is a tribally owned 100 percent Native corporation. We don’t pick a day or occasion to celebrate who we are. We are who we are, so that’s our authentic identity every day. I believe our guests recognize and know and feel this tribal authenticity every time they tee it up.”

That authenticity will again be on display when the country’s finest Native golfers return in October for the 5th Native Open, played on what can only be called a work of art — the Twin Warriors course designed by Gary Panks.

Looking ahead

Before the final round of the Native American Open in 2024 at the Santa Ana Pueblo, as another desert blue emerged from the gold of the early morning sky, Emmett “Shkeme” Garcia of the Tamaya Pueblo gave a blessing.

He led the crowd in a Keres prayer, then his brother Jay offered a translation.

“On behalf of his current tribal chief, and the humble people of the homeland of Tamaya, we pray you watch your words, be mindful of the homeland, remember you came carrying your ancestors and family and friends,” Jay Garcia said. “Be safe, be strong, and be blessed on this special day in this special place. Have a great day and go hard.”

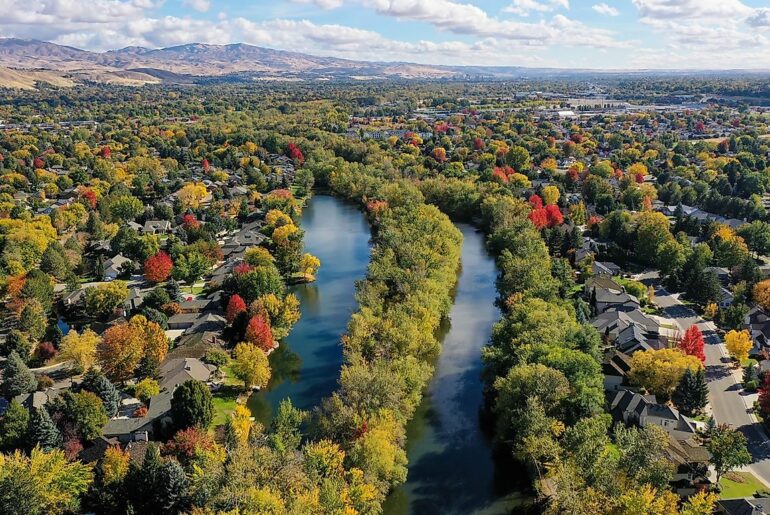

Garcia, the president of Santa Ana Golf, one of five corporations run by Santa Ana Pueblo, then acknowledged the Twin Warriors — Mae’Eqi and Uyuye’ewi — who long ago showed the Tamaya the path to the upper light and the upper world along the banks of the Rio Grande.

“They have led us to our modern existence,” he said.

This year will mark the 5th Native American Open at Santa Ana and Twin Warriors, and is as good a place as any to see how the “modern existence” of economy on Native land includes golf.

All told, we have begun to see a shift in Native economy, and golf is a part of that. In 1992, for example, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin announced it employed more workers in Green Bay County than the Green Bay Packers. By 2017, a St. Norbert College study determined the tribe’s overall impact on the economy in Brown and Outagamie Counties estimated the Oneida tribe’s businesses, events and members — including the magnificent Thornberry golf course — directly contribute $494 million and sustain 3,616 jobs annually. When indirect spending is factored in, the totals rise to $744 million and 5,465 jobs.

Today, golf is a part of this we-are-still-here story. While this may seem surprising, it’s true: golf sits at the intersection of stewardship of Native land, of artistic design, economic endeavor, recreation and wellness, and a means to celebrate Native cultures.

*Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify that Peter Yucupicio was chairman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe when the Sewailo Golf Club opened in 2012. The current chairman is Julian Hernandez.

Dr. Mark Wagner is a golf historian and regular contributor to ICT. His book, “Native Links, the Surprising History of Our First People in Golf,” was published by Back Nine Press in 2024. He can be reached at markgwagner@charter.net.

Related