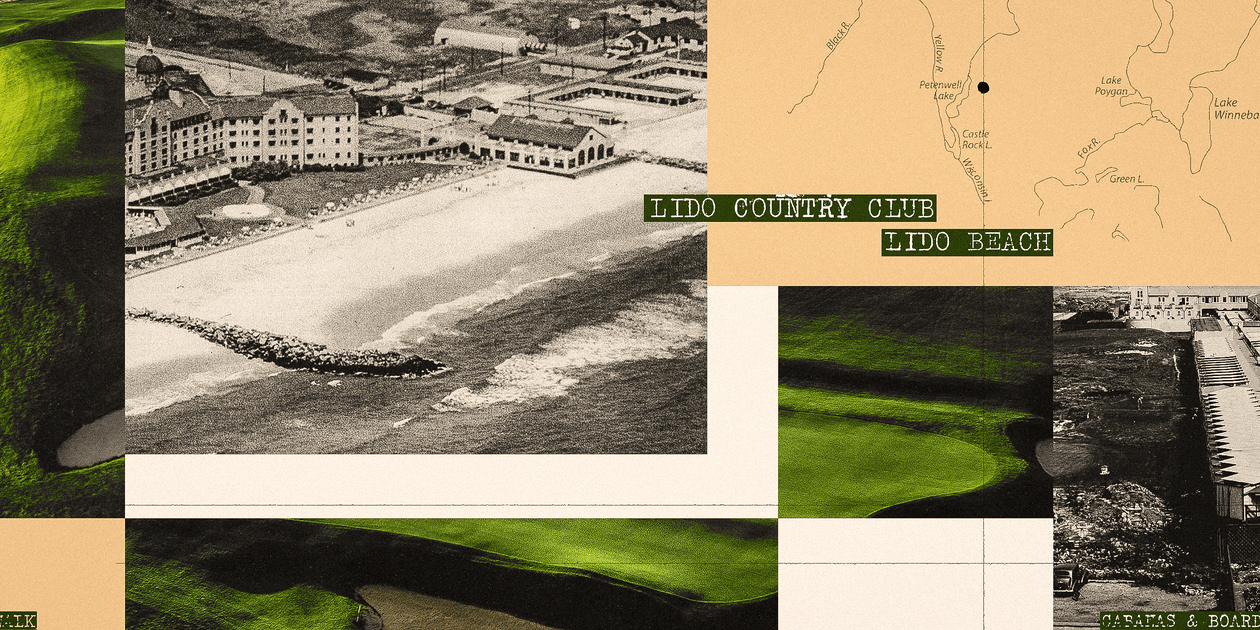

Before all this, the seaside stretch of Lido Beach, a mere hour outside Manhattan, clung to a fading postcard of its former self. The one with new money elites frolicking along the shoreline. The one with flappers dancing the night away, hair bobbed, frills shimmering. The one with the Lido Hotel in the middle of it all — six stories high and flamingo pink. The gall it took to build this thing. A remnant of the Roaring Twenties. Four hundred and forty rooms, a 9,000-square-foot ballroom, the oceanside solarium. The elaborate, rococo-inspired mega-hotel was built by the same architectural firm as the Waldorf-Astoria.

A vestige of what might’ve been, when some envisioned the town of Long Beach becoming “the Venice of America.”

There was little room left in the imagination by the time the scene changed. It was Aug. 28, 1942, when word spread across Long Island that Navy Department officials announced plans to seize control of the Lido Hotel and Country Club and everything else on-property.

“That’s news to me!” its owner, Frank Seiden, told the Brooklyn Eagle.

By day’s end, signage demanded all guests vacate the property within 24 hours. Everyone, including Seiden, did as told. Common along the Eastern Seaboard during World War II, the U.S. military took what the U.S. military needed. The property along Lido Beach was perfect: nearly 200 acres between the Atlantic Ocean and the intracoastal waterway of Reynolds Channel. The land was especially useful to the Navy thanks to ample free space.

That golf course? It could fit a makeshift city of 40-50 barracks and pop-up hospital facilities. All it needed was a few bulldozers.

That is how this all happened.

How the Lido, a golf course conceived by equal parts audacity and genius, one with a story unlike any other, that lived a turbulent life and, in the end, died an abrupt death, came to find immortality as golf’s lost ark, setting off a series of events so improbable that you end up wondering where today starts and history ends.

And how, all these years later, you end up in the middle of nowhere, trying to understand all this.

Exactly where you’d think you would.

Central Wisconsin.

“If he was looking down from the clouds, what would make him grin?”

This is Mike Keiser Jr. asking a question about a man he never met. A man who died in 1939. A man who designed 18 holes in Long Island that turned into an obsession for an army of golfing Ahabs, including Keiser Jr., his brother Chris and their father, Mike Sr.

Charles Blair Macdonald spent 1914 to 1917 building the Lido Country Club, in its heyday possibly the greatest golf course in the United States.

The same course that arrived, or returned, in 2023, as the third layout at Sand Valley, a 12,000-acre golf resort in tiny Rome, Wis.

How? One might call it persistence. Or delusion. The course was built by the aptly named Dream Golf, the ever-growing golf destination enterprise developed by Mike Sr., now shepherded by Chris and Mike Jr. In the early aughts, Mike Sr. grew fascinated with the possibility of rebuilding Macdonald’s long-lost golf course at Bandon Dunes, his sprawling Oregon resort, but ran into two major issues. 1) The Pacific cliffsides were ill-fitted for the course. 2) Not enough was known about the original design to craft a true replica.

Instead, architects Tom Doak and Jim Urbina designed a collection of tributes to Macdonald’s template holes — those the legendary designer considered ideal holes — creating a course known today as Old Macdonald.

Bobby Jones tees off at the original Lido in 1929. (Courtesy Peter Flory)

But the original Lido’s lure kept tugging. The Keisers, especially Mike Jr., couldn’t shake the research compiled for Bandon, much coming from Macdonald biographer George Bahto. The idea of what once was, what it must have looked like, felt like, played like. It was romantic, this idea of lost perfection, like Michelangelo’s David breaking free and going on the lam.

The Keisers weren’t alone. Understand, there exists an entire subuniverse of golf architecture enthusiasts that’d require many thousands more words to explain. Peter Flory, a Chicago-based banking consultant and amateur golf historian, came upon the story of the Lido years ago and, as a hobby, set out to create a working model of the course to play on his golf simulator. In turn, with the help of an online legion, he compiled the largest known collection of photographs, both ground-level and aerial, of Macdonald’s design. Over three years, Flory went on to complete a full 3D rendering of the Lido.

At Sand Valley, meanwhile, Mike Jr. and Chris Keiser set their eyes on a flat, sandy piece of property across the street from the resort, one with distinct wind patterns, as if rolling off an ocean.

As word got around that the Keiser brothers were seriously considering rebuilding the Lido, Mike Jr. was connected with Flory. Then Doak and design associate Brian Schneider came onboard as architects. Using Flory’s models, Schneider programmed GPS bulldozers to replicate even the most minor micro-undulations of the original design.

The plan went forward, despite one notable caution. Mike Sr. had long wondered if a true Lido re-creation was, in truth, a fool’s errand for a destination resort.

He had a point. The course, as originally intended, was to be played multiple times by inquisitive minds. It was meant to challenge smart players with discernible skills, not high-handicappers looking for a good time. As the journalist Ralph Trost wrote sometime in the 1930s, the Lido was “a Robin Hood in reverse” — rewarding good players and punishing bad players.

It was not, in other words, meant for your boozy buddies trip.

The Keiser brothers understood all this. Doak did, too. They built the Lido anyway.

Inch by meticulous inch.

“Because that, in and of itself, is worth doing, because the course was so good,” Mike Keiser Jr. recently said. “But also because, as soon as we change one little thing, we lose all our credibility. Then it’s no longer C.B. Macdonald.”

That’s why, on a hazy summer Sunday morning, you might find yourself out in a disorienting expanse, where you’re unsure what shot is needed next; where from everywhere you can see everything; where the wind cakes sand upon your sweat and the beach somehow bleeds between blades of grass; and where, say around the 11th hole, standing next to a meandering strand of white slat fencing, you say to yourself, “Where the hell am I?”

The Lido is a course that’s still coming to be understood.

Just like the original.

C.B. Macdonald, in fact, wanted nothing to do with any of this. Nearing 60 years old, and plenty wealthy as a stockbroker, he was already considered a founding father of American golf in the early 20th century. He didn’t need the headache of the Lido.

Born in Canada in 1855, raised in the United States, and schooled in Scotland, Macdonald made his name as one of the game’s great early amateur players before turning his interest toward architecture. He studied the greatest holes abroad and implemented their styles — his template holes — to designs in the U.S. To this day, Chicago Golf Club and National Golf Links Of America, both Macdonald originals, rank among the best in the world.

A group of powerful men wanted the land between the Atlantic Ocean and Reynolds Channel to be Macdonald’s next classic. The Lido Corporation was led by former state senator William H. Reynold and backed by the likes of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Otto Kahn and other New York aristocrats. Sure, they wanted a course and club on par with any other, but the real deal was the end game — dicing up the land around the course into hundreds of real estate plots.

It all sounded good, except for the 115 acres of tidal marshland for the golf course. Macdonald told the investors nothing could be built there. But then came their counter. What if $1.5 million was spent on the construction, roughly three times a typical new course of the era? What if the Lido was the world’s first entirely man-made course?

Macdonald years later described growing “fascinated” by the chance to create a course from his mind’s eye. “It really made me feel like a creator,” he wrote.

Macdonald, center, was one of golf’s most brilliant golden age architects. (George Rinhart / Corbis via Getty Images)

Work began in 1914, a mere 20-mile drive from present-day Bethpage State Park, site of next month’s Ryder Cup. The endeavor predated both the town charter of Long Beach and the four-lane, $1 million Long Beach Bridge that would, in time, link the barrier island to Long Island. Macdonald and Seth Raynor, his protégé and chief engineer, filled the entire property with 2 million cubic yards of sand (at 7 cents a yard); sculpting massive greens, careening berms and enormous hazards. In a bizarre twist of unintentional baton passing, Alister MacKenzie, an upstart young architect who would years later create a course called Augusta National Golf Club, won a magazine competition to design the 18th hole.

Then came the hard part.

Golf was, to this point, a relatively new game in the U.S., and the club’s initial members were very rich men, primarily over 50, who weren’t built for blind shots, deep bunkers and ocean winds. One story goes that an early member, after bungling through Lido’s opening three holes, arrived at the famed fourth hole — a split fairway par-5 — and, when presented his option to go right or left, responded that he would, in fact, go backwards, and returned to the clubhouse.

Despite being hailed at opening as an unthinkable feat of engineering, the Lido immediately struggled. Membership numbers sputtered. Some investors hit financial difficulties. Course conditions paid the price.

But then things turned. World War I concluded. The explosion in U.S. automobile sales made Long Beach more accessible from the city. A booming upper-middle class bought seaside bungalows as soon as they could be built. In one sweep, the Lido became the private club in America, its membership ticking up toward 2,000, its reputation growing right alongside it.

One by one, greats of the game came, and one by one, they raved. Gene Sarazen. Bobby Jones. Walter Hagen. Harry Vardon and Ted Ray, the top English players of the time, declared the Lido an equal to any links back home. British golf writer Bernard Darwin, the grandson of Charles Darwin, wrote, “The Lido, judged as a battlefield for giants, is the best, not only in America but in the world.”

Then came the big play — a hotel — seeded by a new group of developers. The six-story pink extravagance was completed in 1928. French windows with white wrought iron balconies. Bronze sconces on every wall. Live orchestra every night. Whatever it took to upstage the likes of Atlantic City and Palm Beach. Lido Beach would be America’s answer to the European Riviera.

In the middle of it all — the Lido.

“A really weird contradiction,” Peter Flory said recently. “C.B. Macdonald didn’t really get the memo that the main intent was to sell real estate, and it’s great that he didn’t, because if he would have built some pandering golf course meant to sell lots or be a resort, then it would have never been famous.”

Problem is, what Macdonald and Raynor built, and what produced profits, couldn’t coexist.

The Lido was easified with every season. More and more, the oceanfront reality became more valuable than the design. After an early storm destroyed Macdonald’s original eighth hole — a lengthy par-3 biarritz running along the shoreline, what Flory calls “maybe one of the best holes ever” — a poorly built replica was put in its place. By the late ’20s, though, the eighth hole was re-routed inland, freeing up the waterfront for more development. As time went on, the Atlantic, once in view throughout the course, was nearly entirely blocked off by cabanas.

An editorial in the Brooklyn Daily Times pleaded: “Golfers of wealth and influence should get together and devise some means of saving the course.”

Wealth and influence? Both took a hit in 1929. The Great Depression would leave the Lido looking more and more unrecognizable, stirring rumors in the early ’30s of it possibly being shuttered and converted entirely into real estate. One last renaissance came at the decade’s end, sparking major improvement around the course, but the advent of World War II ended all of that.

Seiden, only a few years removed from purchasing the Lido club and hotel for $960,000 in 1940, rented the entire property to the Navy for one year. In 1943, with the Navy having transformed much of the land, he sold it outright for $1.3 million.

With that, the short, odd, bedeviled life of Macdonald’s Lido was over.

The new Lido opened in 2023 at Sand Valley. (Brandon Carter / Sand Valley)

On a Sunday afternoon earlier this summer, next to the nondescript clubhouse near the Sand Valley Lido’s first hole, four friends climbed onto a shuttle for a ride across the resort. Shirts untucked, hats perched lopsided atop heads, they looked as if they’d spent the previous four hours lined up against the Wisconsin Badgers defensive line.

“How’d it go?” one was asked.

A loaded question, apparently. The four responded with faraway stares. Having paid $275 apiece for the pleasure of a Lido tee time, the group played 15 holes and called it quits. The course? Too hard. The 30- and 40-mile-per-hour winds this morning? Too taxing. The carousing? Non-existent.

Did we not mention the new Lido is dry? Right, the Keisers, wanting their time machine to be about golf and only golf, have installed a no-alcohol policy. No, it’s not a nod to the course’s prohibition era roots. It is, in fact, a nod to its bundle of contradictions.

The Lido is, at its core, a private club. Between 150 and 200 members, mostly hardcore fans of Macdonald’s Golden Age classic, hail from nearby Chicago and Milwaukee, and from as far away as Atlanta and San Francisco.

It is, at the same time, part of the Sand Valley resort. Restricted play is available for guests from Sunday through Thursday. Many who include the course in their trip understand exactly what they’re walking into. Some don’t.

“Maybe 25 to 35 percent of the guests who play it, it’s their favorite course,” Keiser said. “But at the same time, I think it’s also the most consistently disliked course by our guests. Then there’s a group in the middle.”

Just as the original Lido proved, no course can be all things to all people.

Even on the outside, the highly convoluted world of golf course rankers and raters don’t know what to make of the ghost ship in Wisconsin. It’s long been believed that, had the original Lido design never been mangled, it would undoubtedly stand with the likes of Pine Valley and National Golf Links as the best in the country. So, what do you do with the Sand Valley Lido? How much should it be dinged for not having, you know, an ocean? And whom do you credit — Macdonald and Raynor or Doak and Schneider?

This Lido debuted at No. 68 among Golf Magazine’s top 100 courses in the world and No. 69 on Golf Digest’s list. Too high? Too low? Who knows? At No. 12 on Digest’s top 100 public courses in America, it outpaces its cousins at the resort— Sedge Valley (51), Mammoth Dunes (25) and Sand Valley (12).

At a loss, Garrett Morrison, the head of architecture content for Fried Egg Golf, compares the Sand Valley Lido to “The Grey Album,” Danger Mouse’s 2004 underground mashup of “The Black Album” from Jay-Z and “The White Album” from the Beatles. He’s sort of joking, sort of not.

“It’s obviously an incredible achievement,” Morrison explained, “but there’s also some post-modern bizarreness going on. Here’s this course, brought back to life, in a completely different place, in an altered state. That was the feeling that overcame me when I played it. It was just — this is amazing, but this is so f—ing weird.”

Weird can, of course, mean many things. It’s weird that nothing about the Sand Valley Lido feels counterfeit or synthetic or forced. It’s weird that for four hours or so, you feel like you’re eavesdropping on the past. It’s weird that titans of another time once played the same course with hickory shafts and knickers hiked high. They did, except they didn’t.

A classic Biarritz green awaits golfers at the Lido’s eighth hole. (Brandon Carter / Sand Valley)

Some will get it. Some won’t. Regardless, Mike Keiser Jr. says, unlike the original, this Lido has a clear goal.

“We want to be the most welcoming club in America, and part of that is welcoming guests to play it,” he said. “Most of the membership is proud to be the custodians of this place. I’m sure there’s a silent group of people that don’t express their frustration, but I don’t really care because I know this is the right thing to do. Our core members who play regularly think it’s really cool, and I think we can be leaders in inspiring other clubs to reconsider their guest policies.”

What if that ends up as the legacy of what Macdonald created? Would probably make him smile, no?

The old Lido Hotel came alive again in the 1950s and ’60s. Formal balls and cocktail parties. Gowns and tuxedos. Cab Calloway and Sammy Davis Jr. performing under the open skylight of the Starlight Room, an oceanfront nightclub with a retractable roof. But those times, like the ones before them, passed. The property changed hands again and again. In 1978, what was known as the Lido Beach Cabana Club was up for auction, selling off everything from 6,000 pieces of china to a 1,000-gallon lobster steamer to a Steinway grand piano. The hotel was converted into modern, luxury condominiums. To this day, the building’s pink twin cupolas still tower over the shoreline, surveying the land.

As for the course, over on Long Beach, little of Lido remains. Hope lingered through the ’40s that parts might be salvageable, but by the time Seiden bought the land back from the Navy in 1947, the original design was too far gone. Seiden opted to hire architect Robert Trent Jones to build a new course on an adjacent piece of property, what is now the municipal Lido Golf Club in south Nassau. The 14th hole, a split fairway par-5, is a nod to the old fourth hole. A Sunday tee time runs $43 for residents, $55 for non-residents. Across the street, where the Lido once stood, is now the site of Long Beach Middle School and a public beach for the Town of Hempstead.

So, did C.B. Macdonald’s course disappear? Or does it live?

Hard to say. Maybe it just depends on where you’re standing.

And what you want to see.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photos: Courtesy Sand Valley, Peter Flory)