LYTHAM St. Annes, LANCASHIRE, ENGLAND – It was somewhere just off the sixth fairway of Royal Lytham and St. Annes Golf Club when, lost amidst the heaving sea of shaggy, marram-grassed hills, I felt the metaphoric lightning strike.

It was electrifying how much fun I was having.

I had no idea where the green was; it was made blind by dunes towering above me on all sides. The wind was backing, totally against the normal prevail, gusting in my face when it should have been helping. And the rain fell slightly to the side — excellent, soft English weather.

My lion-hearted caddie, John, and I were enduring three-and-a-half hours of my bogey and sometimes double-bogey golf without an umbrella; he’s a stalwart fellow indeed. He picked a patch of biscuit brown grass for me to play my next shot over. Undaunted by the rain and wind, I hit it, straight and true, and together we soldiered on, boats beating valorously against the current, bound for victory no matter what the odds.

LISTEN TO GOLF NEWS NET RADIO 24/7

FOLLOW GOLF NEWS NET RADIO: iHEART | TUNEIN

That was when I felt as though we were facing Open Championship conditions for certain. The rain, the wind, the heather and gorse, the steep-faced riveted bunkers bouncing my recovery shots back at me, the blind shots to the fairway after drives gone awry — this was what I came to England seeking. I wanted my own Open Championship.

I got it all right; and it was far better than my wildest golf dreams.

If Cypress Point is the Sistine Chapel of golf, and Winged Foot is its Yankee Stadium, then Royal Lytham and St. Annes, tucked cozily in a charming neighborhood just along England’s fabled Golf Coast, is most certainly golf’s Westminster Abbey, crowning the game’s royalty for 100 years. Ancient and venerable, storied and celebrated, the entire experience — from arrival to departure — is truly regal. King Charles himself could stop by unannounced at any time with Gordon Ramsay, Martha Stewart, and [insert name of foreign dignitary] in tow, and no one would find so much as one thread, speck, or grass clipping out of place or order.

Royal Lytham and St. Annes is impeccable; it is perfection in golf, the apex of what any golf club could possibly aspire to achieve.

Yet Lytham, as it is called by its friends, is also a fascinating study in contrast. If the golf course were music, it would be a jazzy, be-boppy a-syncopation. Think Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie. Free-spirited music shattering both expectations and rules: soaring, spiraling high notes and poignant lilting soft-spoken passages – a heart-breaking minor fall followed by an awe-inspiring major lift. Like free-form jazz exploration, Lytham’s golf architecture does not follow rules like the Doctrines of Symmetry and Framing. The result is a course not only unique in the world of golf architecture but of singular vision and critical importance to the craft of golf design. Lytham stands in triumphant defiance over all golf design’s typical rules and expectations.

It’s this devastating synergy of royal treatment and perfection in every detail, combined with brilliantly primal links golf, that makes Lytham not only a quintessential and perennial venue on the Open Championship rota, but one that should be studied and appreciated by all golfers and one that attracts international members from across the globe. Lytham has a charm, an allure, warmth all its own — ferocious golf course aside. That’s why when you come to Lytham, it stays with you forever.

LYTHAM HAS HOSTED 11 OPEN CHAMPIONSHIPS SINCE 1926 WHEN AMATEUR BOBBY JONES PREVAILED. THAT SAME YEAR KING GEORGE VI CONFERRED UPON THE CLUB ITS ROYAL DESIGNATION

LYTHAM HAS HOSTED 11 OPEN CHAMPIONSHIPS SINCE 1926 WHEN AMATEUR BOBBY JONES PREVAILED. THAT SAME YEAR KING GEORGE VI CONFERRED UPON THE CLUB ITS ROYAL DESIGNATION

If some truly great golf courses are considered “a final examination in golf,” then Royal Lytham is an oral defense of a post-doctoral thesis. Even soaking wet and with little to no wind, Ernie Els’ winning score to par par in 2012 was a paltry 7-under 273, just one stroke better than David Duval’s 274 in 2001. [Author’s Note: In the 2012 Open, the par at the sixth hole was reduced from five to four, meaning that Duval’s winning score to par was actually 10-under, still nowhere near the record-breaking numbers posted recently by champions such as Henrik Stenson or Cameron Smith.]

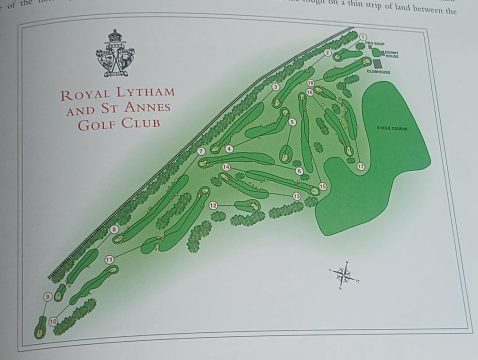

From the get-go, Lytham does things differently, so the golfer must dance to its polyrhythms. Even Lytham’s physical location, one mile inland from the Irish sea, and just abutting the town’s beaches, sets it apart from the other rota venues. At the Scottish rota venues you can stand on some tee boxes and watch the Firth of Forth have a firth-off with the Firth of Clyde or Firth of Fifth or whatever firth happens to be handy. At Sandwich or Deal, you get the iconic White Cliffs of Dover and the mighty North Atlantic. Lytham’s “edge” (as coastlines, lakesides, or other hard boundaries are called in the parlance) is actually the railway line bordering the right side of several holes on the front side, (Nos. 2, 3, 7 and 8). But what Lytham lacks in eye candy it more than makes up for solid, relentless, and authentic links golf.

Yes, Lytham is unquestionably a true links, and don’t let anyone try to convince you otherwise. Linksland often extends for more than a mile or so from the sea, exactly the case with Royal Lytham. The buildings on the sea side of the golf course came after the course was laid out in 1886. Although the course doesn’t touch the shoreline, it’s treeless landscape sits on sandy soil. Both Muirfield and Carnoustie, also seminal rota venues, are similar in that although they also do not touch the ocean. The geologic history of their landscape is the windswept sand dunes upon which the course is built. The same is true of Lytham, always spoken of in the same such discussion as both Muirfield and Carnoustie.

LYTHAM’S BUNKERING IS ITS STERNEST DEFENSE. AWKWARD STANCES AND GHASTLY LIES ARE TO BE EXPECTED, SO PRACTICE UP AT HOME BEFORE BOARDING YOUR FLIGHT

LYTHAM’S BUNKERING IS ITS STERNEST DEFENSE. AWKWARD STANCES AND GHASTLY LIES ARE TO BE EXPECTED, SO PRACTICE UP AT HOME BEFORE BOARDING YOUR FLIGHT

“I am a fan of Royal Lytham,” proudly beams no less a personage than Tom Doak himself, author if the five-volume “Confidential Guide to Golf Courses” and arguably the best golf designer on Earth in the last 30 years. “I find the setting charming, and I think the overall quality of 18 holes is superior to that of Royal Birkdale or Royal Liverpool or Royal Troon or Carnoustie, although it does not have a hole like the Postage Stamp which puts it on people’s bucket lists…it’s all about the golf.”

Ignore any poppycock you hear about how “industrial” Blackpool is, or how the red-brick neighborhood might underwhelm some naysayers, or how the beaches are for vacationers who like to freeze in their raincoats while watching storms roll in off the Irish Sea. The charm of both the twin towns and the club is palpable, the setting idyllic, and you walk in history in every step. So quit making excuses: The golf course will give you enough reasons to bellyache if you don’t get your mind back on the clock and carefully plan your way what many pros and pundits – including immortal golfer Nick Faldo and immortal sports writer John Hopkins both – called, perhaps, the hardest of all Open venues, particularly when the wind blows.

Indeed, Lytham’s three main defenses — and they are stern — are its routing, the wind, and the bunkers, in that ascending order of difficulty.

The routing keeps the golfer off balance. You have to dance a strange but funky asyncopation. Open with a par 3! Three par 3s on the front nine! Back-to-back par 5s! All four par 3s and all three par 5s are completed by the first 12 holes! Then suddenly — WHAM! — Lytham throws six par 4s at you to close, four of which are all you can handle and either into the prevailing northwest wind, or at a crosswind. It’s a cunning use of the endless wind changes, where you get pirouetted like a ballerina, spinning this way and that on every shot on the final six holes.

Certainly, the wind changes everything. True links golf requires so many ore calculations, especially the wind, which will blow 30 miles an hour in a crosswind right during a crucial shot. That’s exactly what happens at Lytham; the further into the round you play, the more the final holes twist around each other. None of the final seven holes play along the northwest-southeast axis of the first 11. Instead, they slash diagonally, some play along a north-south axis (Nos. 12, 13, 14), others at an east-west axis (No. 15 and the tee shot on the dogleg 17th).

“It’s so hard to control the ball in wind that is left to right and into you,” Faldo, a three-time Claret Jug winner, said to Peter Alliss during the 2012 Open Championship broadcast. The routing even criss-crosses at one point, where the 16th and 18th tees meet, another charming architectural feature and one coming back into vogue now that we are solidly in the Second Golden Age of Golf Course Architecture.

AND THE OPEN rota ROUGH IS FEROCIOUS AS WELL. JUST GET IT BACK INTO PLAY.

AND THE OPEN rota ROUGH IS FEROCIOUS AS WELL. JUST GET IT BACK INTO PLAY.

Finally, the bunkering is the beating heart of Lytham’s defense. To date they number 167 strong, actually reduced from the 207 they numbered at their zenith in 2012. Sod-faced and tightly riveted, Peter Alliss described them in 2001 as “197 little ponds,” and he’s not far off. Deep, sharply and steeply faced with round edges frequently leading to awkward stances, and with surrounds that gather even quality golf shots rather than repel them, Royal Lytham’s bunkering makes a strong argument for the toughest on Planet Earth. Full stop. Try to name another course so infamously feared for its bunkering. Not easy, is it?

“The sand is a living nightmare,” Colin Montgomerie moaned in a post-round interview. “Don’t get greedy, get out,” he advised, his frustrated voice a plaintive wail. And whatever you do, do not go “on tilt” and start maniacally flailing away like Phil Rodgers. You’ll take seven to get out, wreck your card, and be left with a silly cautionary tale that was unavoidable had you taken your medicine instead. The fairway bunkers are especially penal, an almost guaranteed pitch out sideways and a stroke irretrievably lost.

Just ask Adam Scott. He dropped a claret jug in one.

“We took out 40 bunkers or so and added four, mostly greenside,” said architect Martin Eber, discussing some of his most recent work at Lytham, on track to host the Open again in either 2029 or 2031, the official announcement from the R&A due sometime in the next year or so.

“What we took out we replaced with shaved chipping areas and hollows, like at holes five and nine. The members are especially happy as they were punished more than the pros by the ones we removed. Meanwhile the pros face a tougher challenge with the chip or pitch shots than being able to spin a bunker shot.”

Although Lytham is considered short for professionals contending in the Open — just over 7,100 yards — Lytham is long for amateur golfers, with the medal tees clocking in at a strong 6,638 yards with a course rating of 74.3, more than three strokes greater than par. There is a friendlier 6,365 yards set of tees for shorter hitters.

“It’s shorter than St. Andrews,” explained John Daly, 1995 Open winner at The Old Course. “But the fairways are narrower.”

In what some consider a bit of mercy, the greens at Lytham are subtle. Far from the sweeping curves of, say, Augusta National, Oakmont, or Winged Foot, or even the solid internal contouring of Royal Liverpool. Lytham’s greens are relatively flat. Carefully analyzing micro-movement is one key; distance control is another. And remember that the wind will affect putts far more on the treeless expanses of links courses far more than in America, so account for that cautiously.

Lytham is a little different, but the golf world is all the better for its creativity and contrarianism. The course’s indelible, unique character is its strength. Quirky interesting and quirky fun, but with an embrace that warmly welcomes like a lover, then coils and suffocates like a python, Lytham requires careful planning and execution. Lytham rewards shot makers, not bombers. Although it does not take the driver out of an ordinary golfer’s hands, there is no overpowering Lytham. Sometimes you bleed shots, they percolate away one at a time. Sometimes you hit the chamber with the bullet in it and the bunkers deal out a horrid number. Again, Monty provides cogent analysis:

“You can talk yourself into an early grave around here,” he noted in a flabbergasted tone of voice. “After one round, you know where not to go, and after two rounds, you absolutely know where not to go, but by then you’re out the door.”

But all is not lost; let’s take a look at how to plan your attack and, if not conquer the unconquerable, at least survive your round with a score to remember.

THE RHYTHM OF LYTHAM

Lytham can be divided into five segments: Holes 1-3, holes 4-5, holes 6-8, holes 9-13, and holes 14-18. (The yardages listed here are from the medal tees, the tees visiting golfers are expected to play, with proper adjustments for handicap, of course. These reflect the 6,683 yards Orange Tees, course rating 74.3.)

HOLES 1-3

It’s time for a safe, sensible start. The first three holes (pars 3, 4 and 4) play along the railway line in a southeasterly direction, and — unless a storm is rolling in off the Irish Sea — they play with the prevailing wind. What you see is what you get, which is one of the other reasons why the pros like Lytham so much.

Lytham shows its individuality at the outset with its par-3 opener. Slightly uphill and surrounded by bunkers, the first hole sets up like a Redan, though there is no kickplate. The green, however, does run away from the golfer, a nasty surprise to those who misplay an early pitch or chip. [Author’s Note: When the course premiered, the first hole was a slightly longer par-4. We’ll delve more deeply into the course’s history in the second half of this piece.]

The par 4s at Nos. 2 and 3 run along the edge of the railway line, with out of bounds all along that right-hand side. The OB is more in play for pros and long hitters, as bogey golfers can easily tack safely to the left, though longer approaches will be required to reach the greens. Fairway bunkers line both sides on both holes, with the third playing 30-40 yards longer and with more trouble behind the green. With a long chain of four deep bunkers up the left side, the drive on three in particular is one of the toughest on the course. The green is raised above fairway level, and two deep pot bunkers flank the entranceway, while another guards long.

LYTHAM’S PAR-3 FIRST, UNIQUE IN MAJOR CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF

LYTHAM’S PAR-3 FIRST, UNIQUE IN MAJOR CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF

HOLES 4-5

No. 4 turns back towards the clubhouse, the only hole on the front that plays into the prevail. Though short, it turns at a 50-degree angle at an awkward spot, where four bunkers and two hillocks all but block the knee of the dogleg. Anything left is a blind approach. It makes a great match-play hole.

The fifth is the first hole to play into a cross-wind should the prevailing wind appear. Usually a mid-to-short iron, the green is deep, but surrounded not only by frighteningly deep bunkers but also by some of Ebert’s new hollows and chipping areas. Avoiding the bunkers is paramount as it can turn this pretty little jewel of a golf hole into the gnarled little grinning garden gnome thumbing its nose at you. One unfortunate sould on our recent visit took five to get out of the front-right bunker and carded eight.

HOLES 6-8

Now come the shakras of the outward nine, where the rubber really meets the road. These are my favorite holes on the entire golf course, and certainly the critical stretch of the front side.

The back-to-back par 5s are markedly different. The sharply doglegging, 483-yard sixth recalls St. George’s with its rumpled “heaving sea” fairway. The recently redesigned 573-yard seventh recalls Birkdale with its fairway amidst newly created heaving sand dunes. Avoid the gauntlet of bunkers flanking the sides like soldiers lined up for inspection.

These two holes were also the focal point of the effort to balance the two nines. With what was once regarded and a much tougher back than front, especially finishing into the prevail, par at Lytham was sometimes described as 33-38 rather than 35-36. The new design of the seventh and the reduction of par at the sixth from five to four supposedly alleviate the perception that one side was far easier than the other. Still, cui bono? Who benefits? And what difference does it make other than artificially reduce scoring to par?

The eighth is likely to be far more difficult for bogey golfers than for experts. Clocking in at just 400 yards, a ramrod straight drive must also be long enough for the golfer to be able to carry the next shot three clubs uphill and over three yawning chasms masquerading as bunkers while threading between four more cavernous greenside bunkers large enough to swallow a golfer whole. A potential drive and pitch for long hitters, average golfers face having to lay up on an already severely demanding hole, then play their most treacherous approach of the day to a green surrounded by trouble. Eight is the unexploded minefield of triple bogeys waiting to happen.

LYTHAM’S SHORT-ISH, BUT TREACHEROUS PAR-4 EIGHTH.

LYTHAM’S SHORT-ISH, BUT TREACHEROUS PAR-4 EIGHTH.

HOLES 9-13

Finally: attack, attack, attack! For the mere mortal golfer this is where to score (or at least limit the damage). For the expert, the respite they felt at No. 7 is echoed in this five-hole stretch.

The tiny par-3 ninth, just 155 yards, is prim as a cameo nestled cozily in a lacquer box, like a treasure to be presented to some powerful potentate. Yet it can be had with a short iron. Bunkers ring almost the entirety of its circumference, yet in an act of mercy for the members, some bunkers were removed and newly added chipping areas provide relief to average players.

“It doesn’t affect the pros, but the members love it,” Ebert surmised.

You turn for home at the tenth tee, and as long as no one loses their drive short and right into mounds of shaggy marram grass or the bunker complex which juts into the fairway, they should have a short iron or wedge in their hand for the approach. The new 11th, like the seventh, was changed to add a new practice area for use in future Open Championships. Whereas seven was shifted to th right, closer to the railway line, 11 was shifted to the right. Neither overly taxing, nor a pushover at a mere 541 yards, the dead-straight hole should yield low scores. Short holes at the par-3 12th and the par-4 13th are similarly welcoming as long as the bunkers are taken out of play.

THE APPROACH FROM THE RIGHT OF THE HOME HOLE.

THE APPROACH FROM THE RIGHT OF THE HOME HOLE.

HOLES 14-18

From 14 on, Lytham throws down the gauntlet. In his “Confidential Guide to Golf Courses,” Doak called holes 14 and 15 “the fifth hardest back-to-back holes in golf.” The narrow 14th plays into a crosswind for a fairway set at a diagonal. The 15th was called by Jack Nicklaus “the hardest hole in major championship golf,” though I’m fairly certain Jack forgot all about 18 at Carnoustie. Still these two holes, playing 434 and 454 yards, respectively, are dastardly holes on which to make 4.

Similarly at 17, the drive must be placed in a tennis court-sized pocket of turf ringed by nine bunkers, the furthermost two of which pinch the fairway to a narrow bottleneck. From there, the hole jumps left through a notch in the mounds of thick rough, playing to a green set at an awkward angle with four bunkers cutting across the front and two additional bunkers behind. A similar tee shot awaits at 18 but with a choice: play straight to the parallelogram of turf set amidst four diagonal bunkers – two on each side. Or play to the right of the bunkers and try to follow the right edge of the fairway for a slightly more direct, but peril-fraught route to the green. In 1974, Gary Player played a recovery shot left-handed with the club upside down from against the clubhouse wall to secure the claret jug and forever enter Lytham lore.